Behind the Mother Goddess

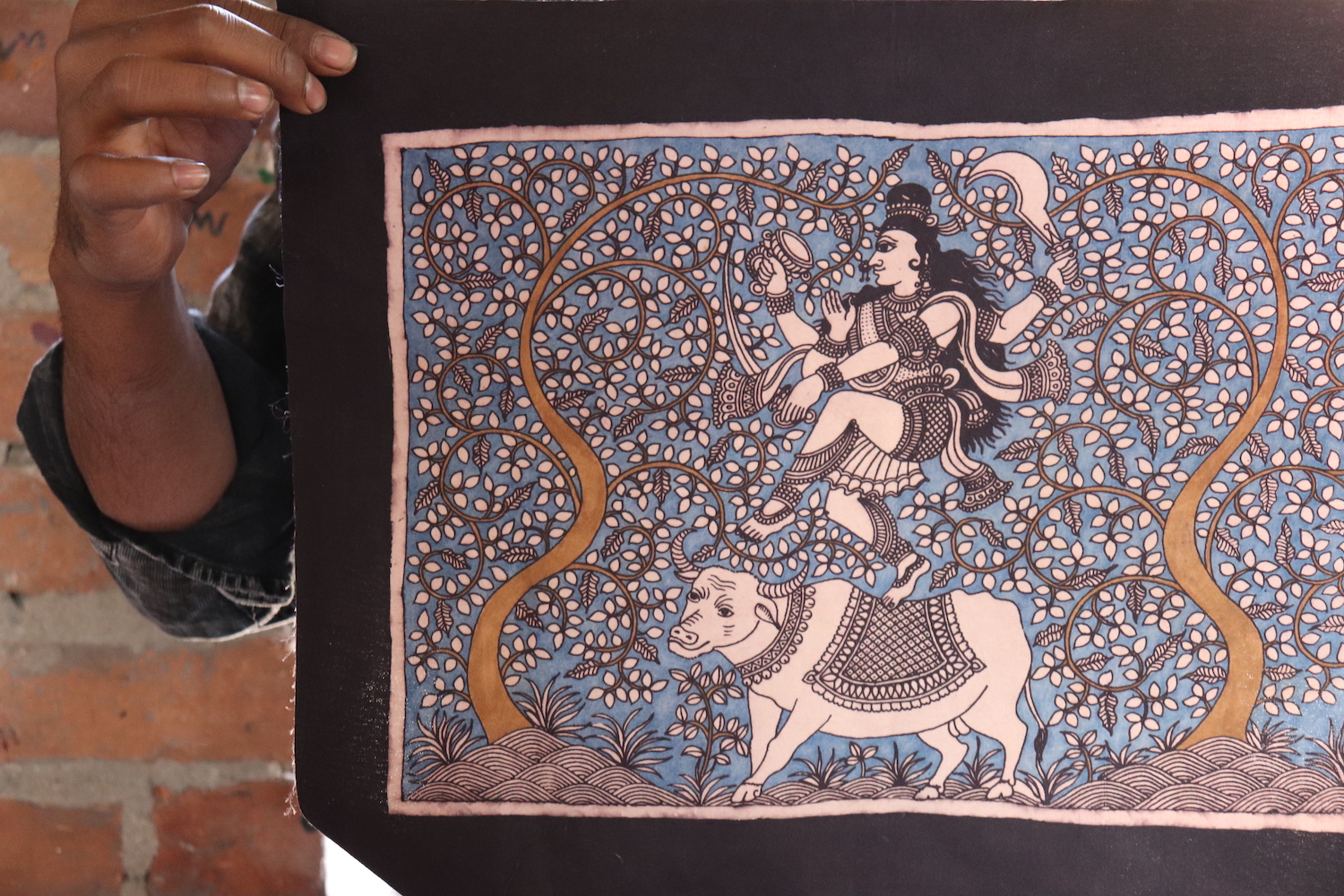

Kirit bhai had a glint in his eyes as he spoke about his works being displayed in a Museum in Japan. He had a dream, and he had his art. With a spirit of a true artist, it was Kirit bhai’s vision that made him stand out. About a 10 minute drive from the centre of Ahmedabad, Chitara family stays in a humble village that is preserving the art and craft of Mata ne Pachedi, also known as Kalamkari from Gujarat, an art form that first emerged about 800 years ago when the Vaghri community was excluded from the social system and was not allowed to enter temples. They painted goddesses on a sacred cloth that was hung behind temples and this led to the them sharing narratives from Hindu mythology and Indian folklore in the form of hand painted drawings. Kirit bhai happens to be the 9th generation of this family.

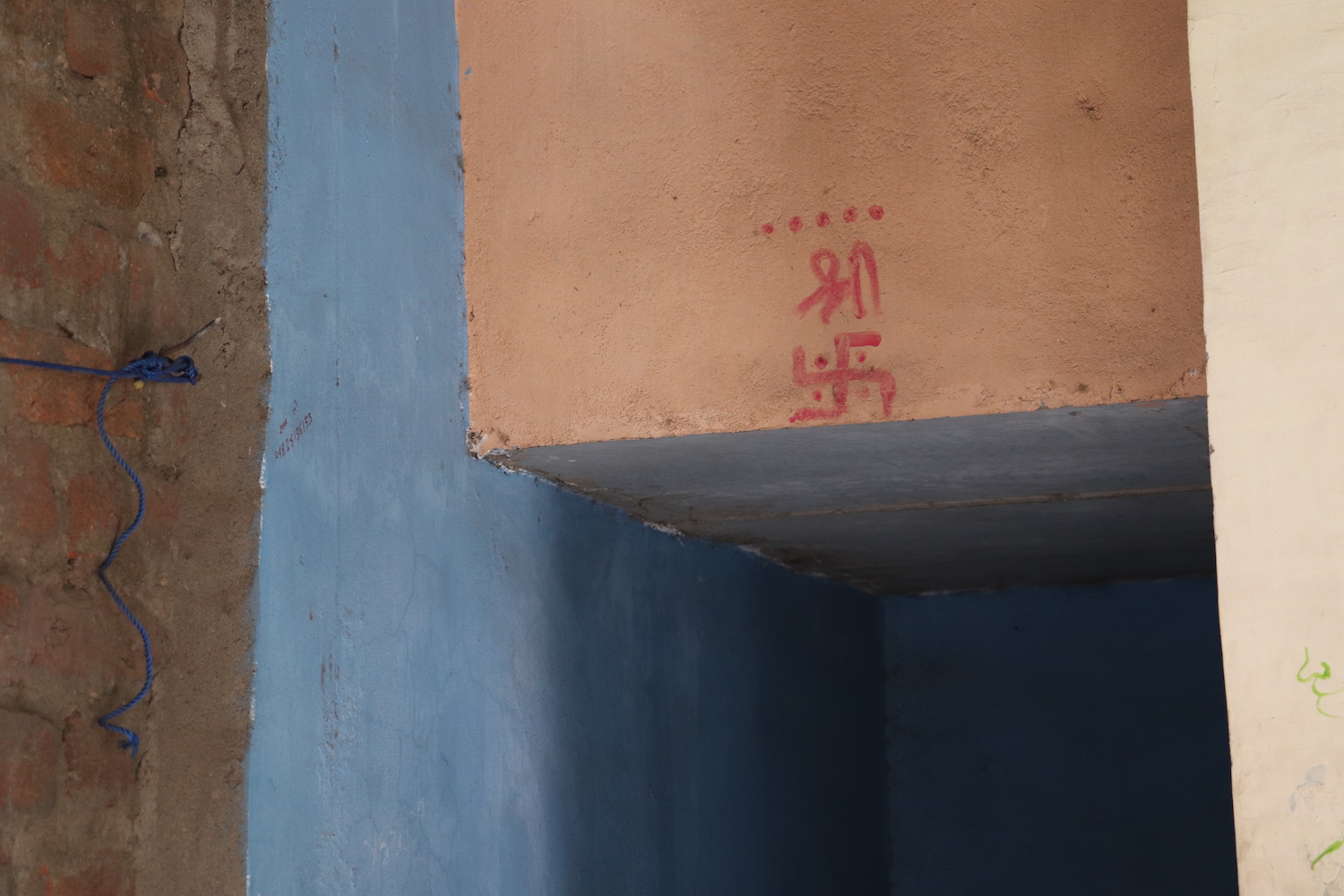

Meeting Kirit bhai happened by chance, as only a night before I got to know about them and I decided to visit them. It all felt like an unplanned mini adventure, where I didn’t know what to expect. Kirit bhai walked me through the lanes that lead to his workshop. Rays of light through the open air workshop highlighted the painted fabric. The space didn’t seem to belong to the city. Layers of white fabric were laid on a bed that was used to paint. Further, Layers of paint had given distinct textures to these undercloths, as if the white fabric was like a soul carrying colours from all the bodies that covered it. It was that hour when warm sunlight seeps through the misty cold of a January morning. Symbols of faith were illustrated on the pink choona walls, making the godly presence more apparent. A cloth that was used by the artist to clean their hands, was art on it’s own, perfectly imperfect. A few women from his family were working a piece with Devi in a war field. Mustards and reds of the natural dye gave the space a warm ambience, merging into the colour of the brick walls.

I knew I wanted to capture the soul of this place and the craft, but the artist himself had a lot to contribute to my experience. His entrepreneurial spirit and honesty made him different from many artists who are self assured and don’t seem to have a vision for taking their art forward. He had a passion to take this little-known art form to an international arena. Generously, he shared his thoughts and feelings about his art, that reflected his sense of pride and ownership. He invited me to his house and introduced me to his family and over a cup of chai, we spent an afternoon conversing about crafts and it’s people. Soon bringing the walls down between a writer and a painter, it was an interaction between two storytellers, two creatives. I was happy he had confidence in me.

Kirit bhai’s father had collaborated with institutions, brands and companies before, however the artist had not receive the credit from collaborators, something that bothered Kirit bhai. How important is validation for an artist? He wanted to be the face of this art-form where the craft and the artist gained recognition. These thoughts provoked me to think what was the future of crafts? The true meaning of preserving crafts? Is it restricted to the tangible material and technique only, or also the stories and sentiments of a community and place? In this context, The craft merely becomes a tool that represents a community. Kirit bhai wanted to work with the traditional methods and innovate them into wearable art, a thought fuelled by aspirations for appreciation, recognition and remuneration. He had worked on a project to marry a Japanese kimono with this technique and also been commission to make scarves for a museum.

The piece of fabric is then boiled in water with mordants, that help it realise its true colours. Like a climax of a film, the piece that looked blackish is now reddish. I believe that the artist brings a little bit of themselves in these pieces, so the art has emotions of the artist as well. A drawing started by his sister, is being completed by him. A collaboration between two equals, brother and sister. This piece that has been worked on by different family members, had a little piece of all of them. There was again a sense of community and collaboration over art.

There is innovation in storytelling as well, for me the wedding scene of Shiv and Parvati in Indigo stood out form the rest. There was a shift from use of reds and also the theme of Devi in the typical sense. Here a goddess was with her masculine other half and a celebratory mood can be seen in the marriage of shiva and shakti.

Feminism was a theme that was explored centuries ago. It still continues to be a theme of exploration through writing, art and dialogue. But for me it was interesting to see this traditional art form being relevant even today. The human connection that surrounds the art was larger than the art itself. The stories of artists needed to be shared as that was a way to preserve the tradition along with the craft. I wanted to do more for the community and find sustainable ways to restore the in equilibrium in acknowledging their art and remunerating them more justly by encouraging fair trade through education and bringing down the middlemen. One way of doing this was simply by buying from them, meeting them, encouraging them and sharing about them. Letting an artist know his worth is one way, I feel.

The craft also brings together a community. I sensed the active and equal participation by the women in the family. His wife had a say in this art. There was a feeling that women were equal. It was both ironic and coincidental that throughout my journey of exploring crafts from East to West in India, I was meeting strong, resilient, creative women and this craft celebrated the Devi, a woman who was both, soft and strong. Kirit bhai's wife, had a calm but luminous aura. She had the kind of satisfaction a true artist has, that is defined by dignity. Her green eyes and golden skin were signs of her subtle beauty. I thought to myself, how it had been a year of Devis, where independent, authentic voices could express themselves through art. It felt like a celebration of womanhood, a restoration of balance in the world of masculine and feminine energies. I was looking forward to meeting more of these women on my journey.

After the space and the artist, it was the craft itself that was the centre piece. I wanted to know more about the process and see a piece come alive in front of me. Kirit bhai explained, that red and black colours were most typically used to paint. The artist holds a bamboo stick dipped in allum and mador ( natural colour to achieve deep red)would begin with drawing the picture from a scene of a story, example Draupadi speaking to Arjuna from Mahabharata. The artist follows his instinct as he/she contributes to flow and the piece comes into realisation by drawing little motifs and filling in spaces with smaller elements. The Kalam, the bamboo stick pen is dipped in natural ink and refilled time to time. Kirit bhai explains that the demand of the market has led many makers to use chemical colours and blocks to make similar drawings. There are 20 family members who draw daily to create works that are commissioned by private collectors, galleries and some craft organisations. Sometimes it takes weeks or even months to complete a piece, thus making it quite expensive to produce and a challenge to sell as well. Thus cheaper adaptations are now in the market, but they have remained ethical and loyal to this art and continue to hand draw( instead of block that the market demands) and continue to only use natural dye.

He feels Devi herself has given them this blessing to keep working with authenticity and take the lineage ahead.

There are a lot of tales and folklore around what is the truth behind the origin of this art, but Kirit Bhai believes that the Vaghri community of Gujarat who were not allowed to enter the temple as they were hunters. It is believed that they could communicate with the goddess and secluded themselves to make them self sufficient. Kirit Bhai shares that the Devi came in his grandfather’s dreams and encouraged him to take on the art form. He says, there are some artists from the community in Pakistan too, as before partition the area of Gujarat merged with the area near south of Karachi.

Kirit bhai drew me a Devi with a sword, and encouraged me to contribute to it by writing my name on it. There was something powerful I was taking back, a spirit of this Devi who held a sword, representing strength but also she was motherly and feminine. This was a precious moment I could frame, almost like a blessing, a reminder.