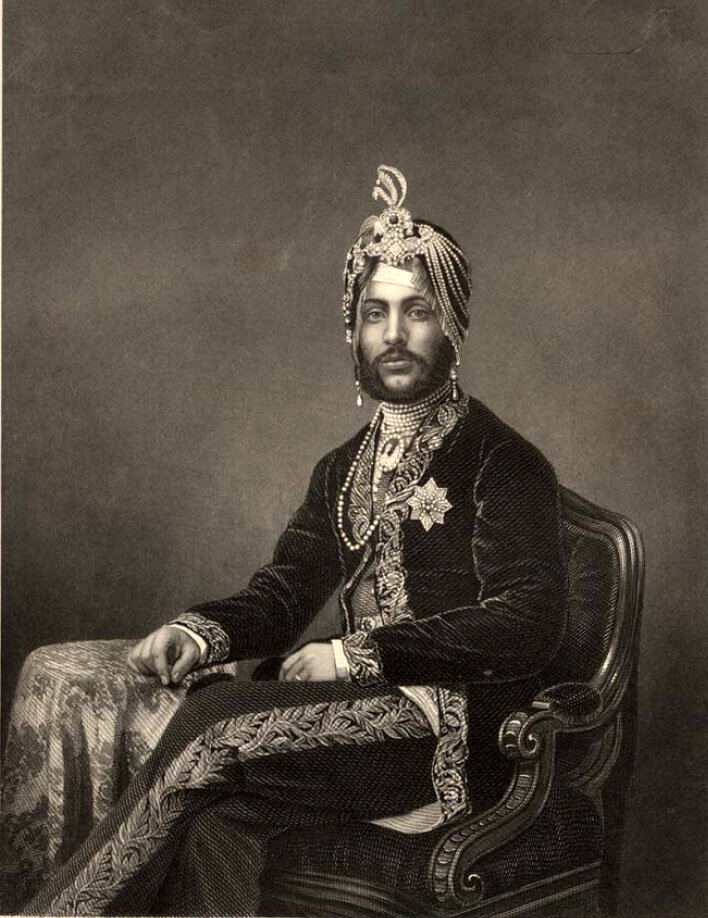

Duleep Singh at Kensington Palace

2019 is the bicentenary birth year of Queen Victoria, to mark this anniversary Historic Royal Palaces (HRP) has created a new exhibition at Kensington Palace. Victoria: Woman and Crown, explores the queen’s private life and her role as a monarch, mother and Empress of India. In order to present a nuanced and complex account of Victoria within the exhibition, HRP worked collaboratively with an intergenerational group of local South Asian community members as well as students from a range of London universities studying South Asian culture and language, to develop a series of text labels in the form of ghazals. It was intended from the beginning that the creative outcome was to be embedded into the final exhibition and lead to a diverse voice and perspective being present in the exhibition narrative.

As part of the exhibition focuses on Victoria as Empress of India, the narrative enabled us to touch upon the story of Maharaja Duleep Singh. Maharaja Duleep Singh was the last Maharaja of Punjab who in 1849 at the age of 10 was removed from Lahore with his title and power devolved. Despite his exile in England and the removal of sovereignty, Duleep Singh became famous as a friend of Queen Victoria. He converted to Christianity in 1853 and then established his family at Elveden Hall, a large stately home designed with Mughal architectural influences, in Suffolk. Duleep Singh became known for his extravagant lifestyle but decided to fight to reclaim his land and title in the Punjab. In 1886 he returned to India where he re-converted to Sikhism. He went to live in Paris where he enlisted the help of Irish revolutionaries and the Russians to lead a revolt against the British in the Punjab but he was unsuccessful in bringing these plans to fruition. He died in 1893 in Paris but his body was returned to Elveden, where he was buried. Many of those in the British Punjabi community have fought to re-patriate Duleep Singh back to India as they believe he was wrongly given a Christian burial in England.

What’s particularly striking about Duleep Singh’s story is the struggle of grappling with identity. On the surface it can be said Duleep was an Indian exiled in England. But what happens to his identity when he has lived most of his life in England rather than Punjab, as is the case with many of those from the Punjabi diaspora. Can he be considered as the first British Punjabi person? He was often thought of as a fashionable gentleman and did well to fuse western tailoring with Indian style as can be seen in his opulent wardrobe, some of which is on display in the exhibition at Kensington Palace, in particular, his velvet jacket and crimson juttis (slippers). Clothing is of course one way in which a person can visually express their identity. Duleep broke away from what was expected of men’s fashion in the Victorian era and made use sumptuous velvets. The crimson velvet juttis were handmade and made use of foliate decorated gold braid work on the exterior and interior of the shoe. The velvet jacket with silk lining was made in England, in a semi European style, which the Maharaja wore on more formal and state occasions. Much of his wardrobe whilst in England made use of tailor made outfits with gold embroidery and rich colours such as purples and maroons to convey that he was still indeed Indian royalty and not just a person in exile.

The struggle with identity is something that is seen so often amongst first and second generation migrants. I have always thought the British Punjabi community have felt such a strong connection to Duleep’s story as we can see ourselves so much in him. Most first generation migrants came from Punjab to the UK in the 1960s and 1970s for economic reasons, with the hope that one day they’ll eventually return. Eventually as the years have gone by, there is the realisation that the UK is now home. As Duleep did with Elveden Hall and his time in the UK, many first generation migrations have clung on to visual aesthetics and material culture to remind them of what was once home. Our homes become shrines to Punjab. Our walls are adorned with beautiful Gurmukhi text and paintings by Sobha Singh, the earthy smell of chandan burns every morning, our wardrobes are full of vivid colours, gota prints and malmal fabric. Parents regularly handing down traditional Punjabi food recipes to their children as well as stories about Heer Ranjha and Sohni Mahiwal.

Paying homage to the homeland isn’t something that is only confined within domestic spaces. In towns such as Southall, the Punjabi community have created a microcosm of their motherland. Shops regularly stock their shelves with spices, lentils and mithai. Temples are erected, displaying the architectural majesty of North India which in turn becomes a space for bringing the community together in a safe environment. Women regularly jostle down the street dressed in their finest salwar kameez’s with glimpses of tila-kar and mukesh embroidery under their big winter jackets. The latest Bollywood hits of the day were also shown within the town’s local cinemas attracting over 8,000 people weekly during its height of popularity in the 1970s and 1980s.

Alongside the tangible aspects of bringing Punjabi heritage to the UK, the intangible heritage comes along to. Wedding customs such as, boliyan and giddha (traditional folk singing and dancing) fill the atmosphere during times of celebration. Families revel is carrying out a Jago ceremony (a ceremony by the maternal side of the family announcing their arrival through song, dance and decorated water pots carried on their heads) out in the streets ensuring the whole neighbourhood is aware a wedding is about to happen.

In a world where everything is globalised, we have surrounded ourselves with Punjabi culture in hope that it does not get lost in the past. Much like how in the past, Duleep Singh clung on to visual signifiers of his Indian and Punjabi identity, the same can be said for the Punjabi diaspora around the world today.

Words Jatindey Kailey