Heirloom | From Punjab

Every piece of heirloom tells a tale of generations. It is a tangible reminder of our regional, cultural and linguistic lineage, preserved in stories and objects of material memory that provide great nostalgia as the years go by. But even nostalgia aside, heirlooms simply convey the importance of the individual or the social microcosm of the family in the larger dialogue of cultural anthropology, wherein the significance of material culture is understood in larger, more cumulative settings. Heirlooms provide that intersection between the personal and the cosmological, the private and the public, the intimate and the extrinsic. Which makes them not only multitudinal but also elusive, embracing many definitions at once.

Thus, heirlooms make a most interesting area of study, and one that demands the attention of anthropologists, academics, and creative alike. They have in them embedded the nuances of preceding generations and how they operated in the everyday world through the use of seemingly uninspiring things. They also are rich sources for contemporary design cultures to engage with and reiterate the past in newer, meaningful ways.

Intangible heritage

The realm of the private, away from the prying eyes of the public space, went unacknowledged for the longest time in terms of topics demanding careful assessments and creative studies. The increasing interest in oral culture, however, over the past decade or so,

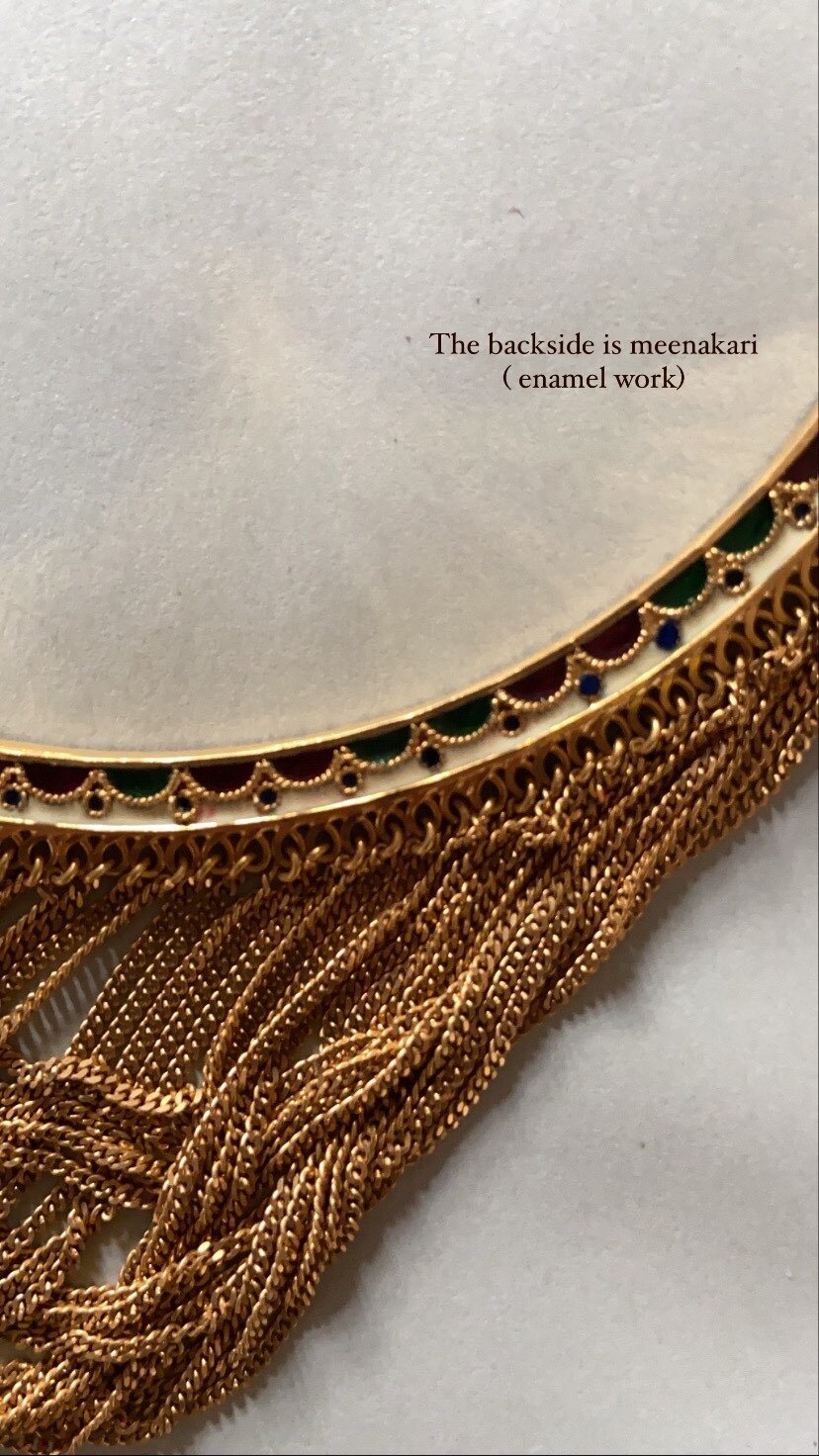

made the ‘home’ and the ‘oikos’ a potential subject of investigation. Because heirlooms are more often than not objects hailing from the home space and have carved in their atoms the language of intimate relationships, feminine bonds, and the power of memory and remembrance, they continue to fascinate students and scholars of cultural anthropology. The materiality of heirlooms aside, which comprise its own narratives, it is their intangible aspects that defy the time-bound palpability and rise to abstractions. For instance, the relevance of design thinking vis-a-vis heirloom pieces in textile or jewellery has enthralled creatives forever. The curiosity of past attachemnts, of motifs and patterns, of what emotions they meant are an enigma better understood in suspension.

From mother to daughter

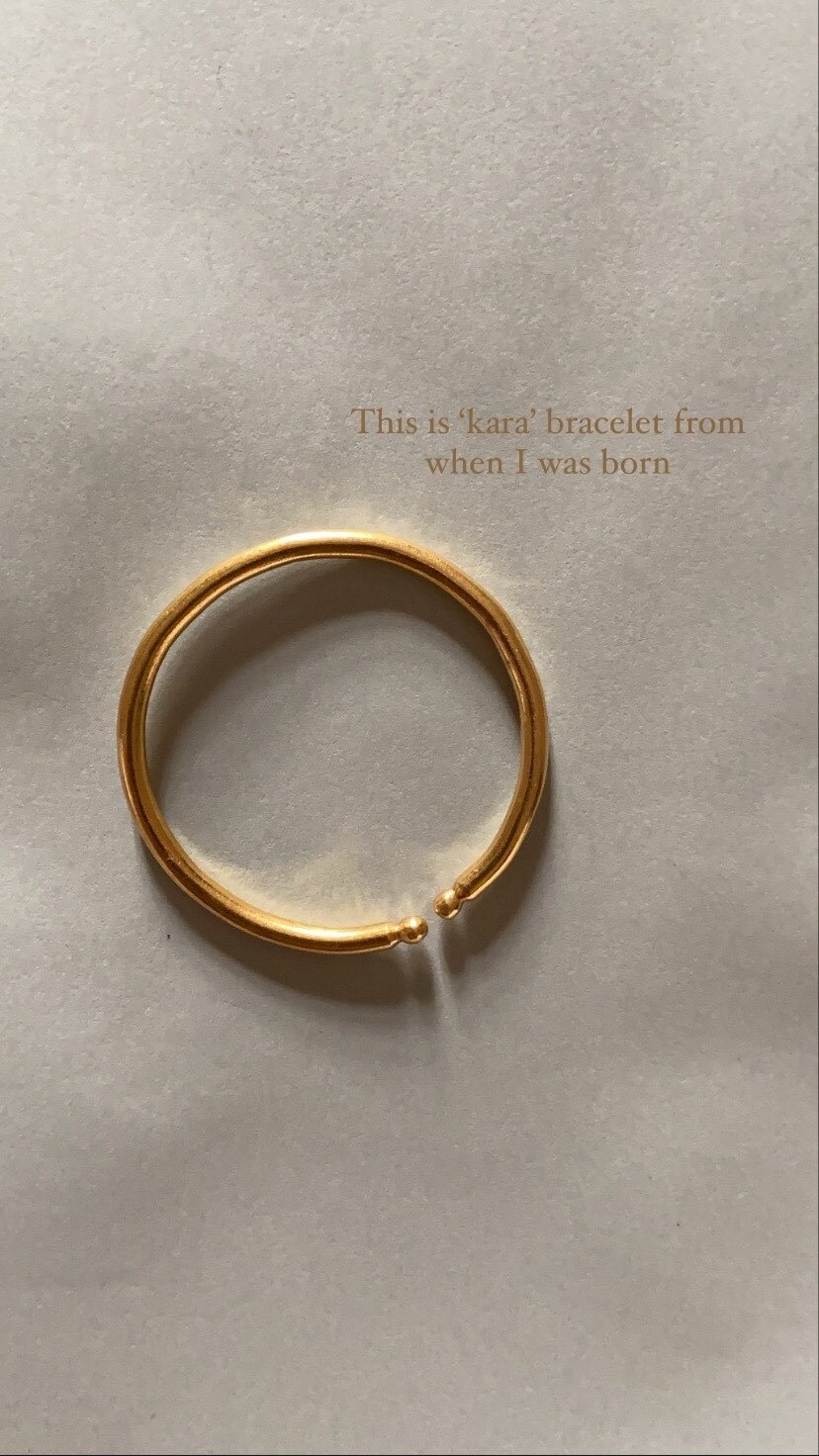

In India, heirlooms have been passed down from generation to generation since ages, and continues to be a very prevalent practice even today. A marriage ceremony is incomplete without the passing down of a generational from the mother’s wardrobe to the daughter, or that piece of coveted gold jewellery. It is the uncontested rite of passage for so many young girls to womanhood. For so many of us, the first saree we possess is a piece we inherit from our mother or grandmother; in weaving cultures, it is a common tradition for the elderly women in the family to weave the girl her first piece of traditional cloth (like saree or mekhela sador) upon attaining puberty. Could we safely relegate the deep importance of heirlooms and the rituals associated with it – of creating, preserving, and inheriting – with the liminal space of women? Is the culture of heirloom not inherently sustainable?

Reliving eras through heirloom

As a little girl, gazing at your mother’s beautiful Banarasi saree while she carefully pleats it to perfection is a form of love language difficult to capture in words. The way in which we relive old times, our own childhoods or those of our immediate families and friends, takes place through inherited objects from those eras. Brass utensils in the kitchen worn soft with time; tumblers with the edges blunt from use; furniture that have names crafted in them to speak of untold legacies; or jewelleries with designs hard to find a trace of in the present times. The past becomes readily accessible through these objects carrying not only memories but also meaning and identity, such as we start living through them and find ways of connecting the dots of our own lives through them – whether lived or imagined.

Colours as heirlooms

For the millennials, a generation witnessing the pleasures of both social media and pre–

social media days, the 90s aesthetic comes revisiting in robust and ‘regal’ ways, through colour palettes that were typically present in the world around; on streets, on the television, in weddings, and in closets. If you were to capture an entire decade in one shade, what would it be and why?

The desi Rani Pink. A shade between hot pink or fuschia and red, seen on the screen, at weddings and celebrations, on furniture, and even on the walls. We remember this colour from the 90s, the growing up years of so many millennials newly enthralled by the excitement brought about by Cable TV and globalization.

It is as if this vibrant pink rightly spoke to the aspirations of the times, the desire to stand out and to be seen. From the Queen in Carrom, the rich pink Ruby gemstone, to the reflection of its usage amongst Indian royalty, the name may owe its allegiance to timelessness in Indian design history.

Possessing a piece of heirloom is like wearing the past against your skin and recreating its spirit. They are essentially a tool of remembrance and reiteration. The distinctive designs of handmade crafts, achieved through years and years of dedication and practice render them timeless and a rare. When we heirloom pieces today, we represent not only the glorious craft practice of those before us but also the legacy of the common women who wore them and cherished them and made them their own.