In Conversation with Oral Historian, Aanchal Malhotra

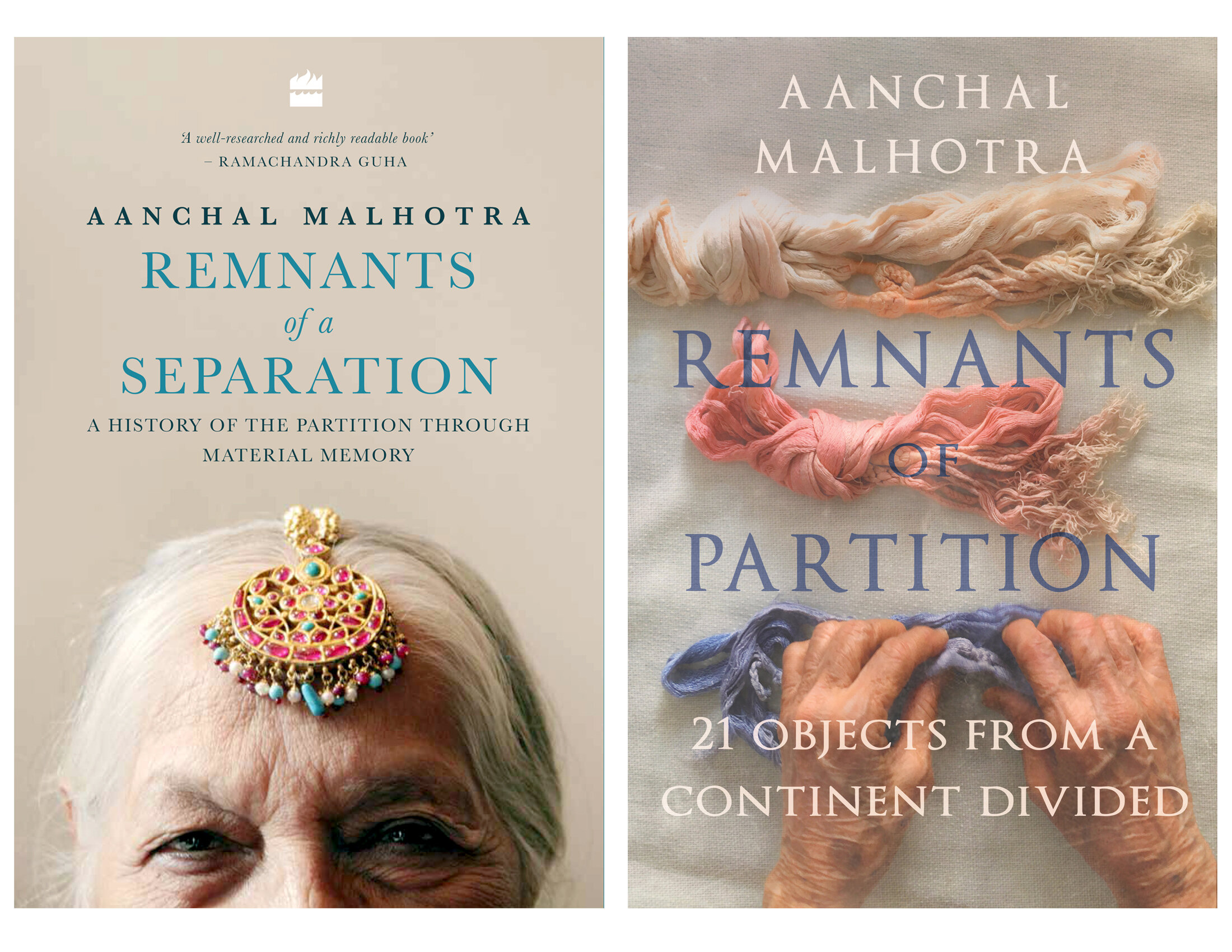

An author and oral historian, Aanchal Malhotra’s debut novel Remnants of a Separation: A History of Partition through Material Memory is a moving exploration of personal stories of the journeys made across the Radcliff Line, during the 1947 Partition of the Indian sub-continent. Her work is a ground-breaking milestone in the socio-cultural ethnographic study of the greatest migration in history. She is the co-founder of Museum of Material Memory, a digital repository that archives antiquarian objects, family heirlooms, and ethnographic narratives.

Aanchal spent her childhood surrounded by family lores of Partition and the power of the written word through her association with Bahrisons Booksellers— founded by her paternal grandfather Balraj Bahri. She is currently working on the release of her next two books, titled The Language of Remembering and The Book of Everlasting Things, to be published by Harper Collins India.

“People build their own fantasies about what the other is and the other is also a built human construct. We are essentially creating the other out of fear of something we don’t know. ”

You studied in Montreal and that’s when you started your research, but tell us what your inspirations were to research on this particular subject and why does it feel so personal to you? Are there any particular incidents that inspired you? I know that you are very close to your grandparents, tell us how it all started?

I am close to my grandparents, but any work of this nature has to go beyond the personal into the collective. So, I think that the reason for starting the work was the realization that despite many of us in the subcontinent being born under the shadow of Partition (that’s not really a topic that any of us can escape if we born in India or Pakistan), we know so little about it. There is little tangible, real information about it. We depend even 7 decades later on the official history and the official number and the official sources. Then what will happen to the subsequent generations and their knowledge about it? Their knowledge will just keep getting reduced to a point, where it is almost diluted and the individual person that migrated from one place to another has been rendered invisible, almost.

One thing that I noticed in the official study of the Partition is the predicament of the individual person is given very less importance in comparison to the politics of that time and it seems rather unfair, because the individual person was the one that bore the brunt of what happened. To migrate from one place to another with either lack of knowledge or resources was very difficult in those circumstances. Though we have archives interviewing people and recording stories they are not for the study of the memory. They don’t really go into the detail of why someone feels the way they do or how it has affected the subsequent generations. They are archives for the purpose of archiving, so that we have it for posterity.

My interest was — why have we not tried to understand or untangle, what Partition means to many of us? How can someone who is born in the subcontinent, still be so removed from it? If we don’t consciously think about it there’s no reason for it to affect your life! So, I think that was some of the beginning thoughts I had, mostly because I didn’t know enough about it and I thought that was kind of amazing that I had grown into a 20 something year old person and just couldn’t explain to someone what exactly had happened. People still cannot explain, even I cannot explain, what exactly happened! But at least now after doing so much research I have a more nuanced view of the possibilities of what happened and the different perspectives that came about at that time.

You just answered my second question: that you chose a method of collecting information which very personal. Oral story-telling through objects is not something that was done before. The museums abroad have archived personal stories, such as Holocaust Memorial, where you see personal objects. Your stories have captured that aspect for India and Pakistan. What do you think like makes this relatable to the wider audience? Why do you think this method works and initially were there any challenges with this method?

Now that years have passed, everything I would say is in retrospect and with the advantage of more knowledge. It is safe to say that at the beginning, as it is with any project and any person, I had no idea what to do. There wasn’t any model for me to follow, the only models that I had were people like Ritu Menon or Urvashi Butalia, who I knew had done this. However, you have to make your own methodology in the field, you can’t really follow someone blindly because that is their method and despite how many conversations I have with them, my method will always be different from theirs. There were oral histories, it’s just that they were not written by someone my age. When we think of historians, we think of a very particular age bracket, we think of a particular gender, we think of a particular construct of education that has been undergone to achieve that status. As a young woman who was moving from the fine arts to ethnography or anthropology, I was challenging all of that.

I think that there is a great misconception among people that the Partition happened in the middle of August and that was that. I think that it happened on 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th … those were the days when it happened and that’s that. In fact, that’s impossible because Partition took months. Some would say years to build up to that moment of division and subsequently it took months and years to normalize, whatever the word “normalization” means to people. So, what we are trying to understand really from that time is daily life. The everyday life of a person and how that was fractured. How can you possibly understand daily life if you don’t talk to people about their daily life, about their customs, about the things that they used, about the friends that they had, about the languages, newspapers, radio programmes, about how they wore their hair? One of the questions in my “questionnaire”. (I don’t really have a questionnaire, because I change it every time. When people go in with a questionnaire about “how old you were at the time of Partition, what happened, tell me about it…” then your conversation may be limited).

I went in asking “When you were a child, did you wear a salwar kameez or did you wear frocks?” People though these questions were ridiculous. “Why do you care about this?”

I care because it tells me what kind of family you came from? Why do I care about what language I spoke at home? - It tells me about the kind of education you may have had. Similarly with objects - what and how much you carried with you can tell me about the status of your family and whether you knew Partition was going to happen.

So, I think that I was trying to understand was social ethnography, the lived landscape of the people. How that was fractured and how that was remade?

At the very basic rudimentary form of these conversations, there was human emotion and despite the fact people may not have witnessed Partition or may not have had people in the family who witnessed it (by this I mean people who are specifically from different parts of India, Pakistan, and the world, it is still possible for people to relate to these experiences because they are about human emotion. Everyone knows what loss feels like. Everyone knows what some form of displacement feels like. Whether it’s moving from one city to another, one apartment to another. Everyone can relate to the kind of precious nature of an object that has been passed down from your family. Everyone knows what that feels like. What I was trying to get at was a human history of Partition, told through a third-generation perspective, looking at how Partition has impacted me. It was always really important for me to bring it into the present, to bring it into my voice, to bring it into the voice of people my age. What have we inherited?

Were there any challenges in terms of a sense of responsibility that comes when you are telling other people’s stories? What approach did you have? Do you want to speak about one or two challenges specifically related to this?

I think that a sense of responsibility comes pretty early on in the project, if you are sincere about it. If you honestly believe in the integrity of the conversation you will automatically be responsible for things that you are hearing. Not to mention that the things that I was recording, may have been the things spoken for the first time. If someone is opening up to you about their lives in such a vulnerable and forthcoming way then the least you can do is to have the responsibility to accurately tell the story from their perspective. It may not be a narrative that you would agree with and that has also happened to me, but it is important to tell their story in the way they have told it to you.

The challenge was really making sense of things, because I was really young when I started and I think that I didn’t quite understand what it would do to continually do this kind of work. One thing it does, is that it makes you grow up, really quickly!

I suppose you have difficulty in relating to silly things or futile things and this is very unfair because this is something I see with myself that if this was like a very frivolous conversation then I would be like I can’t, I am sorry. It’s a bad side-effect that is present in me.

The other challenge is of being a young woman researcher out in the field, and this was ever present. Because no matter how independent you maybe, no matter how financially secure you maybe, no matter how many connections you may have and how many interviews you may be able to collect on your own, there will still be challenges because you are a woman. This is not going to go away anytime soon for people.

I can so relate to this.

I think a lot of female researchers do, and I think that the challenge makes us rise above it, may be much stronger than men at times, because we have to work so much harder.

There is also the distinction between oral history and official history and how this is like a softer kind of approach to history. But I don’t like the fact that oral history is relegated to a soft approach or history from beneath. It makes it sound like as if someone is looking down on us from above. In fact, oral history is the history of people, and people make history. I don’t understand how this could be given secondary importance to anything else. The challenge is also officiating my medium, which I think, I have been able to do successfully for a large extent because of the kind of story-telling that has emerged from it.

My next section is from a digital cultural landscape because especially after Covid, we are spending so much time online. Do you think that something has shifted the way we are consuming stories in terms of its impact. Do you think it’s good that it is reaching a wider audience or do think that the impact is distilled due to spending so much time online?

I think people may have a little more brain space during this time and they may not be suffering from compassion fatigue, when you are inundated with so much content – particular emotional or traumatic content- that you couldn’t care less about anything, but I don’t think that is happening as there has been a surge in the quality of story-telling that is coming our way. Not just the object but the time people are spending on writing about them. People are more interested in family history and cultural history. I don’t know what is happening but the time people have now, is giving them more perspective about things. On a personal note, I am completely inundated. I have not recorded any oral history during this time. But we have received an enormous number of really incredible stories, which we are continually impressed by.

Any one particular story that has stayed with you? I know this is going to be a difficult question to pick one.

Everything stays with you in some way or the other, they just impact you differently. I keep going back to the stories, I have kept in touch with all of them. You spend time with them, you have visited their houses, and you know their families… It’s just good manners, you know, to keep in touch with them…not to mention the fact that you have written a book with them in it. To spend so much time with someone and to know them intimately.

These days I have been working on the Hindi Edition and I have written a new preface for the regional language specifically. That has really made me think about the interview process and how my own methodology has changed so much since I started. When I started off I was in Canada for about 8 years and I would find it very difficult to connect with people in regional languages, my own languages. You have been living outside for so long, you may not speak Hindi or Urdu or Punjabi that much as you like to at least. I remember my first few interviews were in English and bits of Hindi or Urdu. Now after so many years of having done this work. The entire interview is of Hindi or Punjabi or Urdu and I can’t imagine thinking about it in English, even though I will write it in English. I think this is a very interesting distinction in terms of language and the cultural landscape of home.

I noticed even with people that I interview sometimes, with my grandparents for example, my grandfather only speaks to me in English but every time he spoke to grandmother it would be in Punjabi. I thought that was a very interesting cultural shift that he made. That being said the interviews can still be partly in English but mostly in regional languages, as far I can help it, in whatever languages people are comfortable with. The first time in went to Pakistan, I wasn’t so comfortable in Urdu. So a lot of my interviews were in English… in that sense I was grateful that I could translate them to English but now I think that I am more comfortable with the language of the land, with the language of the soil, the heart! When I was interviewing an Englishwoman, a couple of years ago sitting in the British library, (her father had been in India and she had been in India at the time of Partition), I just found myself grasping for words because although she was speaking to me in English, in my head everything was in Hindi, or Urdu, or Hindustani and I had to translate it to English.

The landscape of the Partition was nestled in the regional!

My next question was that you actually went to Pakistan, so would you like to tell me a little bit about it? Any particular experience that has stayed with you? Not just about interviewing people but being in Pakistan.

Pakistan is exactly like India. There’s no difference. Yet, at the same time there will always be differences if you look for them. The only thing is that I wasn’t looking for them. If I had gone there with a preconceived notion about what I may find or if I had gone there with a certain fear because of the media, then I may not have had the experience that I had. I think because I went full of curiosity, I didn’t know what I would get there but I knew that this was a really important trip to take as this was the perspective that needed to be told and recorded. It was kind of amazing that I wasn’t scared at all. I don’t remember feeling fear. If you think about it - you are 24 years old, and you go across the so-called “enemy line” or “sarhad paar” or “us taraf”. I just feel like it’s so amazing that I wasn’t scared because I was so excited.

Meanwhile, everyone that knew I was going was terrified. Everyone except my immediate family. My parents had been to Pakistan before for work, my grandparents were from there. In fact my grandmother’s brother told me that he wanted Peshawari chappals from Anarkali. He told me the specific store. I said, “66 years have passed, so they probable shut down”. He was confident that they are going to be there and sure enough they were there. The media narrative that has played down on both sides is not without its truths on both sides, but that’s not the only aspect. I think the politics of both countries dominate how they are covered in the media. The truth of the matter is that when it comes to the common people, there isn’t that much difference. You think that people on the streets would have asked me all sorts of political questions, but no. Do you know what they asked me? “Why don’t you wear a saree? Where is your bindi? Why aren’t you wearing jewellery like the way in the TV serials? Why are you speaking out language? What is the price of potatoes? What is the price of onions?” That what they really wanted to know! That’s what they cared about. I am sure they care about other things but in that moment that’s what they asked me. A large part of my work is trying to normalize the word ‘Pakistan’ and that will only happen when you know about the daily lives. I think what will help relations between India and Pakistan is the easing of Visa restrictions. The minute people can travel to either side to actually physically see with their own eyes how things are it will ease so many tensions between people.

People build their own fantasies about what the other is and the other is also a built human construct. We are essentially creating the other out of fear of something we don’t know.

My last question is what does a writer’s day look like? What are you reading are there any favourite places in Delhi?

Pretty boring. A writer’s life is difficult. People may think that it’s easy to put things down on paper. For me, it’s very hard to satisfy myself in my writing. I think a lot of people find it may be easier to write for other people, but that’s not true happiness. For me, it’s very important to be excited while I write, completely absorbed by it. If I can write something, read it 4 months later and still be interested in it, then that’s good writing for me. But a writer’s day is hard. Some writers never read when they write. I am the opposite, I need to read. Also because I write history so I read about that time for research. But I would say my day depends on whether I am writing or researching. If I am in a research phase then I would probably be reading most of the time which can seem like I am doing no work. I am also a copious note-taker and I find that very helpful because when I write things I remember them better and I write everything down. But when I am writing, I usually write towards the night because that’s when it is quiet. Although, I have written during the day in the lockdown since streets have generally been quieter. But last year I would when I working on my manuscript, I would write from 10 pm to 3 am and Delhi was the quietest then. I have a habit of writing certain chapters in longhand completely and then type out. When I was doing the fieldwork on Remnants, I was would record audio and as our conversation recorded, I would start to take notes about the person, how they look, what their gestures are like. How their language changes, or the tone or the intonation or how the light changes around them or how they move. These were the things I was very interested in, because it builds the space for the reader who is not going to there. So, to invite someone into the landscape you need to build the landscape and I try to record all these as my building blocks.