Looking at Looking: Atul Dodiya's 'The Gatecrasher' at Vadehra Art Gallery, India Art Fair

At Vadehra Art Gallery, Atul Dodiya presents a body of twelve oil paintings that quietly but insistently turn the act of viewing back onto itself. Across the exhibition, figures are shown looking at artworks, standing in galleries, hotel interiors, or ambiguous architectural spaces, absorbed in acts of seeing, remembering, and translating what they encounter. While Dodiya has returned to this motif intermittently over decades, here it appears with an unusual intensity and concentration, becoming both subject and method.

At the heart of this exhibition is a deceptively simple question: what happens when we look? For Dodiya, looking is never neutral. It triggers memories, associations, fragments of language, sometimes conscious, often not. These mental movements, he suggests, frequently arrive in linguistic form. Gujarati, his mother tongue, shapes his everyday thinking, while English often intervenes when he thinks about art. This slippage between languages mirrors the way images themselves behave: carrying residues of other images, histories, and sensations that enter the painting almost unannounced.

Several works unfold through such associative leaps. In one painting, the back of a woman with her hair tied high unexpectedly evokes Shiva. Rather than resisting the association, Dodiya allows it to enter the work, inserting a specific image of the god, eyes closed, facing the viewer, while the human figure turns away. The result is a quiet inversion: the divine presence refuses to look back, suggesting a “third eye” that remains inward, withheld. Elsewhere, inexplicable elements such as a sudden golden form against a dark blue wall appear without rational justification, even surprising the artist himself. For Dodiya, this surprise is essential; without it, a painting has little reason to exist.

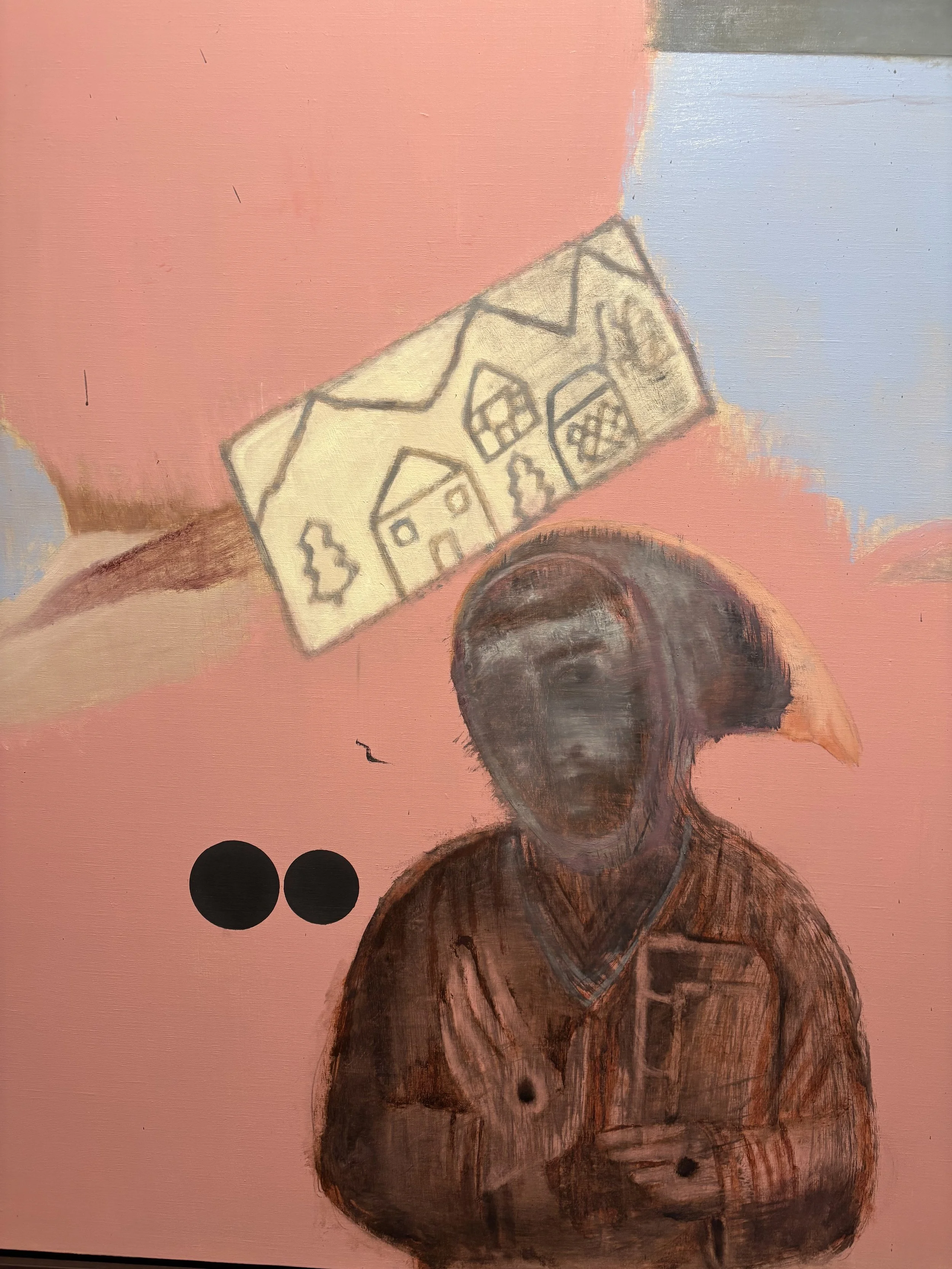

Art history moves fluidly through the exhibition, not as quotation but as lived memory. A painting inspired by Bhupen Khakhar shows a woman identified as Anju Dodiya looking at Khakhar’s work, while subtle references to early Italian Renaissance art emerge through gestures resembling stigmata. Only later do two muted grey circles enter the composition, hovering like binocular lenses or wounds that double as instruments of sight. These additions are not premeditated but instinctive, arriving months after the painting’s completion and shifting its emotional register entirely.

Throughout the exhibition, Dodiya insists on the primacy of the pictorial. Subject matter alone, he argues, guarantees nothing. A grand theme can result in a weak painting, while something as modest as two bottles on a table can achieve greatness through attention to composition, tonality, and touch. His meticulous awareness of brushwork, scale, and surface is evident everywhere: walls bleed into frames, shadows remain unresolved, and tonal “mistakes” are deliberately retained to allow visual movement rather than closure.

One of the exhibition’s most striking works revisits a small archival photograph of Amrita Sher-Gil exhibiting in Lahore in 1937. Here, Sher-Gil looks at her own paintings, folding the exhibition’s central motif back onto an artist who was herself negotiating belonging, authorship, and geography. Rendered with charcoal and oil, the work draws on Sher-Gil’s declaration that “India belongs to me and only me,” while subtly echoing Anselm Kiefer’s later claim, “I hold all of India in my hands.” The painting becomes a dense convergence of personal memory, historical displacement, and artistic inheritance without ever resolving into a single statement.

Dodiya resists the pressure for art to perform activism or explanation constantly. While deeply aware of political and social realities, he maintains a deliberate distance from journalistic modes of representation. His commitment is to painting as painting to joy, difficulty, revision, and visual surprise. He speaks openly of works that caused him trouble and others that came easily, valuing both experiences equally as part of a long, disciplined practice.

The exhibition’s title, Gate Crasher, offers a fitting metaphor. Borrowed from Henri Rousseau’s wedding scenes and filtered through personal anecdotes and friendships, the idea of the gatecrasher becomes a stand-in for the artist, the viewer, and even the borrowed image itself. To look for Dodiya is always to intrude to enter another’s image, history, or memory and make it momentarily one’s own. In this sense, every viewer who steps into the gallery becomes a willing interloper, invited to participate in the quiet, complicated pleasure of looking at looking.

Sayali Goyal in conversation with Atul Dodiya