Journey of Maheshwari Cotton Silk

The Beginning

Along the river Narmada, lies Maheshwar, (two hours south of Indore) a princely town that thrives on its handloom industry. Ahilya Bai Holkar could be called the mother of Maheshwari sarees. During her reign of 30 years in the late 1700s in Maheshwar, she encouraged weaving of cotton silk sarees that had simple patterned zari borders and two pallus. These were naturally dyed and were nine yards long. It is believed that weavers from Mandu migrated to Maheshwar after the Mughal era ended. Today, this cotton silk textile is traditionally woven with zari border and one pallu, with decorative and figurative patterns.

Rehwa

Two centuries later, in 1978, Richard - descendent to Ahilya Bai Holkar - and Sally Holkar paid a visit to the fort at Maheshwar, and realised that they needed to revive this craft. An initial grant allowed the formation of Rehwa society, named after the river Narmada, which trained 12 weavers on 12 looms. Ganesh, who was one of the first few members of the society, had his mother and grandmother (nani) teach the women to weave properly and to prepare their warps for weaving.

“These women had barely any garments to wear; and came to the centre sheepishly. They often came hungry because they had not been able to light fires to cook their food. They had nothing but sticks to light for their cooking; and often the sticks were too green to burn,” says a spokesperson at Rehwa.

The women worked hard and soon the store room at Rehwa was stocking up, when John Bissell of Fabindia became one of the first supporters by selling these sarees at Fabindia's Delhi store. Kamala Devi Chattopadhyay, a legend in Indian textile history, too helped Rehwa to have its first exhibition at Cottage Industries in Delhi. This was the start of a journey of 40 years and still counting.

Rehwa’s main objective was to revive the dying craft to generate income and employment for many weaving families. It grew with time and ventured into health, education and housing for the handloom weaving community of Maheshwar.

WomenWeave and The Handloom School

In 2002, WomenWeave, a charitable organisation was formed to support the role of women in handloom weaving.

I visited the Gudi Mudi Khadi unit, to meet Sally Holkar who shared her perspective on changes and development that have come in the weaving communities in these years and also the vision to take this initiative forward with design education, designer collaborations and open doors to new markets.

“I have been involved in the handlooms of Maheshwar since the 1970s, and have had enough knowledge of the traditional cotton silk texture of handloom. I felt at this stage of my involvement that we needed to look at the younger generation of weavers and initiate crossing borders intermingling of designs and ambitions and histories,” says Sally Holkar.

Luxury and Collaborations

WomenWeave is now working on collaborations with luxury brands and designers as there is a need for the product to be available to the high street and easy access to people in larger cities, however, it is crucial that the product is positioned as a luxury product for the weaver to be able to earn a fair price. Also, it is important that the consumer understands the value of a skill-based quality product and thus engage in buying less over quantity of affordable products available. One of such collaborations is with Good Earth, as it offers both, a deep knowledge of craft and access and understanding of the luxury market.

“I think we should applaud loudly about the product and whisper a little about the backstory of rural India. If one buys into handloom, they should aspire to buy it for the value the product adds and not just because they want to help a weaver,” says Sally Holkar.

Sustainability

Speaking of sustainability, economic, cultural and environmental sustainability are looked in context to the weaving communities, as true efforts are being out to work in ethical and fair trade environment and also preserving cultural roots. Some of the products are being made in natural dyes, however, it is four times more expensive to produce with these dyes, thus making it even more expensive and sometimes less practical. Thus finding a middle path has been adopted by using less harmful dyes that also make the product functional.

David adds “I would say the artisanal sector is at this point lagging behind the industrial sector in terms of awareness and efforts toward improvements. H&M for example is one of the world's biggest users of organic cotton, which, by the way, is only 1% of cotton production. As we know, there are all sorts of problems in the supply chains that are out of the control of artisans. I’m staying at the moment above a dye house, the best in town, but their polluted water still goes, at least until the town or the dyer gets around to building a filtration plant, right into the river. Making a handloom fabric from those yarns does nothing to mitigate the unsustainability of that problem. The survival of handloom has been hitched to fashion. Fashion, as we know it today, is the epitome of global capitalism, and capitalism is all about beating the other. I think it is probably inherently incapable of avoiding exploitation. This is to say that I’m not a believer in the idea that we can shop our way to prosperity and equality. To me, “fair” and “ethical” are marketing terms that, in best case scenarios, mean less unfair and less unethical. A conclusion of my dissertation is that WW is a good, honest, useful enterprise, and its products are symbolic of those ideals — and that in itself might also useful in terms of changing mindsets — but I don’t use words like “slow”, “sustainable”, “ethical” etc. because they are out of touch with environmental science and overblown vis-à-vis the wealth of the producer in relationship to the wealth of the consumer.”

Amba

Named after the river Narmada, Amba is a social enterprise that masters traditional techniques of weaving Maheshwari silks and innovates contemporary designs that suit the taste of a modern client.

Driven by Hema Shroff Patel, the founder and vision behind Amba, the team is made of young enthusiastic weavers, who challenge themselves to create thoughtful collections every season. Their ‘Krishna Leela’ collection inspired by the elements and colours of Bundi Palace in Rajasthan as well as the ‘Weaving Ancient Urban Stories’ that was inspired by the Indus Valley civilisation, caught our attention with their detail and mindfulness seen in design.

Hema has been working in Maheshwar for over 28 years and has also served on the Women Weave Charitable Trust advisory board for 17 years and worked with Rehwa to revive classic Maheshwari sari designs.

“I started Amba as a response to what I was not able to find in the market. I was looking for contemporary Indian textiles with a rooted origin. And I thought I could do this in Maheshwar. We began small with only kurta pyjamas made out of Maheshwari cottons, using the simplest of borders. The stoles and shawls that followed were my response to the big pashmina silk boom in the late 90s. I found them very flat and uninteresting. I wanted to create texture and interest with different fibers using our very small border details” - says Hema

After understanding the beginning, revival and innovation in Maheshwari textiles, we spoke to Hema and her team at Amba studio to understand the workings of a designer brand that caters to a niche micro audience and also the joy of working with young weavers.

Quality Process of a Luxury Product

Speaking of the evolution in weaving, 40 years ago only 4-5 colours were used, only in 48 inch width fabric and one inch borders. But slowly, customer interactions made us innovate and cross our creative boundaries. Hema remembers that there was a huge discussion on the length of the warp change in 1998/99.

“Today we have come a long way in terms of changing of attitudes towards innovation.” says Hema.

Hema shares that re-interpreting traditional designs with a contemporary value is the key to making Indian textiles more relevant in today’s world.

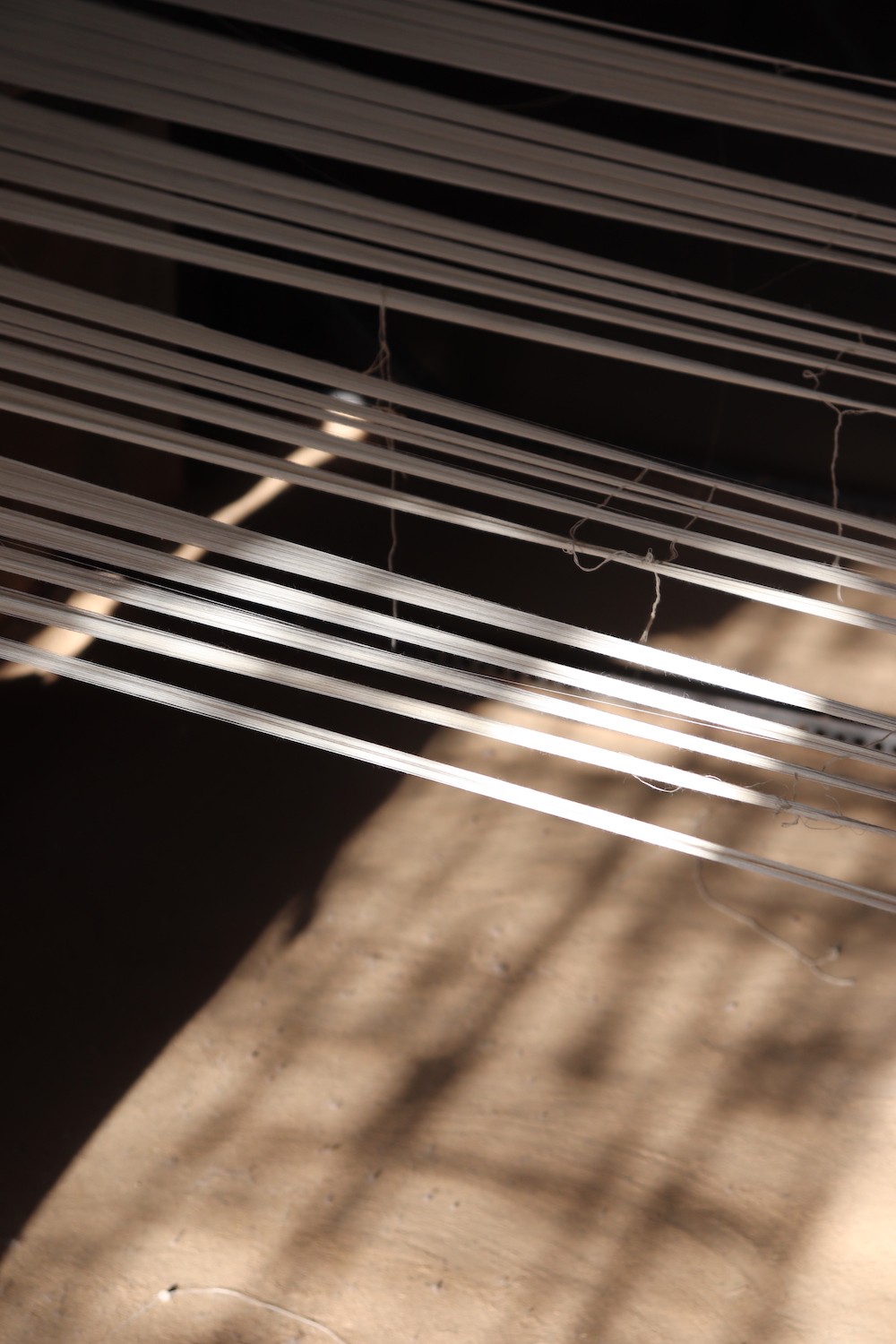

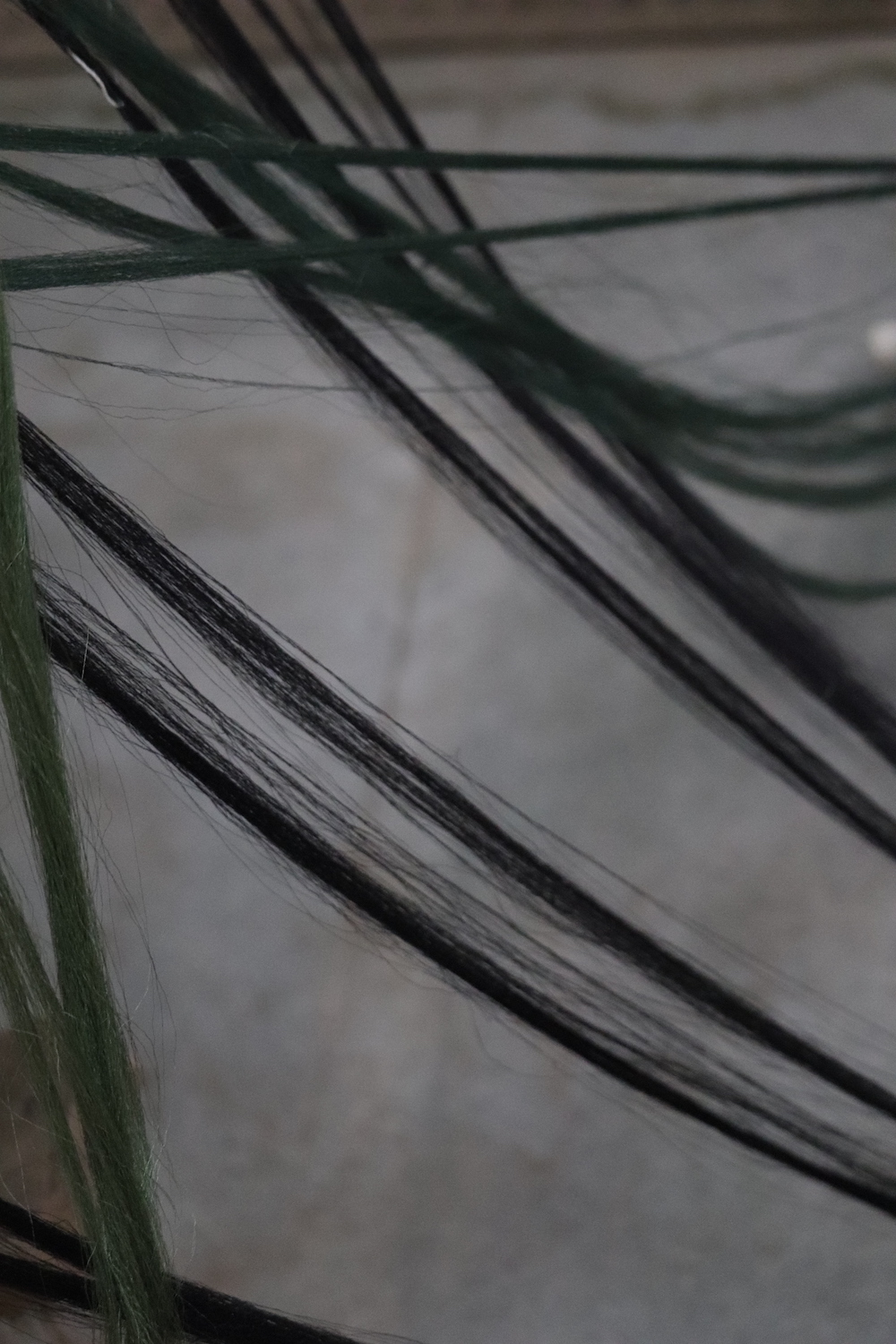

“At Amba, the textiles are woven with refined yarns, in which some cases we natural dye these yarns. A stringent quality control process is undertaken and many post production processes contribute to the final ‘hand feel’. The most valuable and complex shawls take fifteen days to go through the entire process. From hanking the yarns, to natural dyeing them, setting the yarns on the loom, weaving, and then finally the hand finish hem – a total of five pairs of hands will have engaged in creating a very special shawl or stole. These can only be marketed at a higher value”.

The design process is also very detailed as it begins with a conceptual idea based on a theme. Research is then conducted on the theme which involves looking for ideas that will translate into weaves.

From there, a sampling process gins, after which fine tuning the samples before the final production. The entire process from conceptualisation of the concept to production is almost nine months long. One concept a year with two capsule collections – Autumn and Spring are produced.

Indian Crafts representation in the West

Hema feel that good quality and contemporary textiles that have a story behind them are key to finding buyers in the west. For Amba, ‘word of mouth’ and an expat community following form key clientele. Since Amba is a micro label, it is choosing not to scale, but instead showcase exemplary craftsmanship. A creative way to create work throughout the year is by working with small design studios and producing for them.

Sustainability

India has been sustainable traditionally. It is industrialisation and globalisation that resulted in increase in demand and thus unethical ways of production and consumption. Because of the sustainable talk that has been floating around the fashion industry, craftsmen have regained this knowledge and have become conscious.

“I think some craft is scalable and therefore can go to the high street and some craft is meant for high end fashion ateliers. But what is important here is not to dumb down the craftsperson. In West Bengal, so many weavers have been dumbed down because scores of Japanese designers came to Fulia over many years to have their very minimal ‘less is more’ textiles hand woven there. Many of those textiles look absolutely homogenous. The highly skilled weaver who wove fine yarns and knew intricate Jamdani techniques no longer has that same magic in their hands.

Most designers don’t work with artisans to collaborate, it’s a different culture. Here the artisans are part of the enterprise and equals.

“I feel hand to mouth living has to end which is a product of mass selling., thus B to C selling is more fruitful in context of sustainability as we limit the buying power and thus are able to create something of quality which is ethical as well.” says Hema.

'A piece of craft, is both a work of art and design'

“Craft has very blurry lines between being a work of art and design. Uncut textiles like sarees and shawls fit in this category. When one has the privilege of seeing some of these textiles come out of archives, one can hardly imagine that these textiles were actually draped and worn. ”- says Hema.

For more information, Visit: Amba, Rehwa, Women Weave

I walked out of the Badi, the residential complex, in the fort, through a gate onto a sloping road. Overlooking the river and a temple, is Rehwa’s Unit One. The sounds of looms and shuttles signalled that I have arrived at the right place. A central courtyard allowed natural light and air into the workshop. I met with the team at Rehwa, who walked me through the unit and introduced me to the weavers. Currently, Rehwa is formed by 110 weavers and has trained over 2,000 weaver families in the last four decades, who have ventured out to start their own unit. I was excited to know about Chandra Bai, one of the few weavers from the early 80’s, still worked on the same loom. I spoke to a young weaver, Kiran, who is a mother of three and has been at Rehwa for 7 years. She expressed because of training in this skill, she has been able to independently support her children’s education and also has housing at a subsidised price.

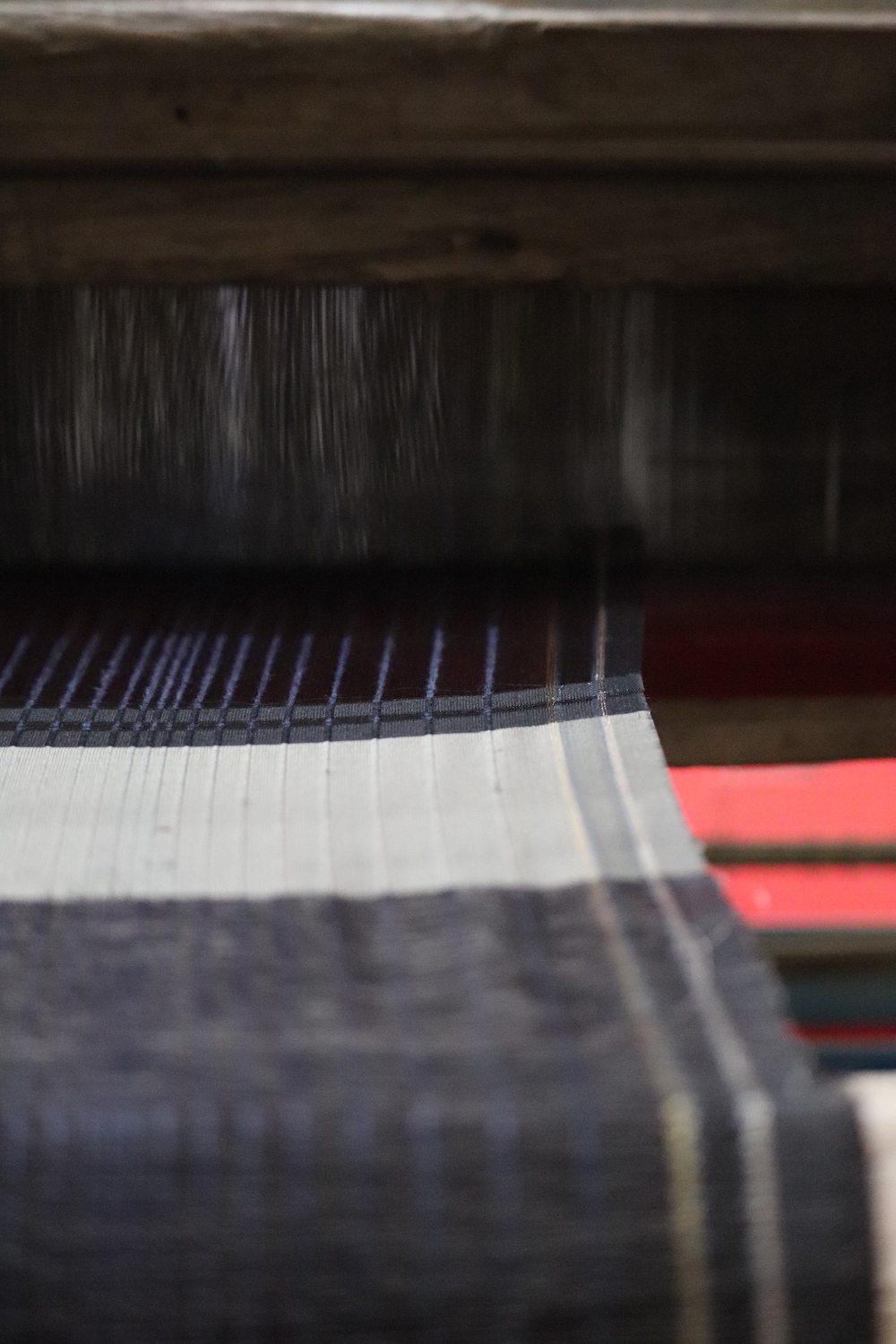

Rehwa mostly weaves traditional designs with bold colours and patterned borders. Most design intervention is done for clients who work with organisations such as Oxfam from the UK and Inis from Switzerland. Some interesting designer collaborations have also happened. Designer Muzzafar Ali created a collection with the weavers at Rehwa in the 90s. Most of the in-house sarees retail from the shops in the workshop complex. It was interesting to browse through the Rehwa saree border catalogue, a renaissance project conducted by the team to archive the traditional designs.

Contemporary Design and Traditional weaving

The Handloom school started in 2016 to train young weavers from marginalised circumstances to become weaver entrepreneurs.

Traditionalist may not be open to the idea of innovation and changing design and colour, however, the vision for the future was to innovate and bring new ideas and collaborations to the forefront. Six-month courses are offered at the Handloom School to both male and female students from 12 different states (mainly Gujarat, Bengal) who are brought together via Weavers' Service Centres (started by former prime minister Indira Gandhi), who have access to local communities in each state. The course offers learning about costing, pricing, presentation, design, marketing and business management.

“A great deal of sharing happens that results is great textiles and innovation. I feel a lot of people are hesitant to revisiting traditional designs, not understanding that these traditional designs were interpretations of a certain time capturing certain synergies, the same way, evolution needs to be presented in design today too and today’s synergies have to be represented through textiles,” says Sally Holkar.

There is technology involvement in the teaching process where the young students can use these facilities to their benefit without losing their roots that are in tradition. The Handloom school is able to provide them opportunities that encourages them to stay in this line of career than choosing something which might pay them more at the cost of leaving weaving completely. The result of this training has led to some of these weavers weave for big designers because of their understanding of contemporary design. The courses are in Hindi and English because of which north Indian weavers are a majority, but the Handloom School wishes to open another training school in Bangalore to accommodate weavers from southern states.

David Goldsmith, (a PhD in artisan fashion) who started teaching English at the Handloom School in 2006 (as it is the language of commerce, fashion, design with the intention of helping artisans see more clearly and interact with the world market) further adds to the conversation of contemporary design intervention to traditional weaving.

“The women of WomenWeave, have better economies, better social lives now than they did before joining the organisation, and this hinges on the design of the product, as well as the design of design of the enterprise. Given global economic realities, handloom is a luxury product. Since people with money tend to buy things that they like, and that almost always means things created with contemporary design-consciousness that most craftspeople lack, designed goods are the key to open the market. Alternatively, “authentic” craft that is beautiful within its own terms, is not that easy to find, in my experience, because it has been degraded over the decades” says David Goldsmith.

Indian Craft in the West

“We want to work in the areas where no one is going. We want to give work to weavers 365 days, make products of high quality and sell at a higher price too. Probably, outside India directly to customers who can value this product. We also wish to combine silk, wool and cotton in natural dyes in collaboration with designer, which means this product would be truly special but expensive and for a special client,” says Sally Holkar.

Textile as Art and Design

“I rarely see craft (particularly contemporary craft) that I think rises to the intellectual level of “real” art — even if craft can be exquisite and awe-inspiring. I see art and craft as different animals living in the same territory. They sometimes co-mingle, they might even mate, but they are not the same. We should also consider design, in the way it is normally understood today: as a highly conscious, deliberate, focused and formalised effort to envision a new product. That has little to do with the way traditional, or generational, craft evolved informally over long periods of time, trial and error, long apprenticeships, etc. So no, I don’t think craft is both a work of art and design,” says David.

Understanding the Young Weavers

“There will be beauty and soulfulness in handloom, that power loom will not have . It will be dull” says Wasim Bhai.

Wasim, a third generation weaver trained himself just watching his parents weave. Since he was 15 years old, he has been weaving and contributing to the family income. Wasim is a collaborator at Amba studio along with his father Basheer ji and other weavers. He lives in the weavers colony that was built by Rehwa Society, as a social welfare project and has 37 homes given at subsidised prices.

He recalls helping in small processes like setting up the loom when he was 8 years old. Wasim’s Grandfather was a turban weaver and a dyeing master. Basheer ji being over 60 years old now, recalls his father teaching him, which means the family tradition has been alive for over six decades. Wasim came across as enterprising and open minded. He has the technical know- how of traditional weaving and likes to interpret a contemporary design that will work well with the technique. For him, collaborating with Hema and for other clients has been fruitful as he feels he can learn new things everyday. In 2014, Wasim researched about Rabindranath Tagore and his multi- dimensional work inspired him. He interpreted his research into denting( lines texture woven into fabric), and also developed it in a range of colours for the Amba collection that season.

“My interest is in innovating, but tradition is in our roots. So we try to find a balance” says Wasim Bhai.

In 2009, Wasim attended The Handloom School and understood the value of his craft. He is able to understand the pros of the trade as there is flexibility in his working hours, there are clean workable conditions as compared to a factory worker, he can stay with his family and it’s not as physically hardworking as a farmer’s job. He further shares a story of his colleague, who got accepted in a leading fashion and textile college and is now working in Ahmedabad with a designer. He says that the friend shared his knowledge with all other weavers, which is a sign of the progress that the community has made as a result of learning and education. This has resulted in motivation to go further and create more opportunities for themselves. He was happy that the ladies of this family can also make a contribution by helping in finishing, cutting and tassel making.

“We hope to have a client who can enjoy our tradition and understand the craft. Money follows. We are happy that the young generation is involved and is encouraged. We need more storytellers to spread the word so people are aware of out craft” - says Wasim Bhai.

Wasim shares that the use of technology is another factor that has evolved the working process. He says he is inspired by seeing works of other weavers on Facebook, and interacting with co- working on WhatsApp has made the process faster. He also shares an experience of meeting a weaver from Chanderi that resulted in experimenting and creating something new. However, there are pros and cons to that as people identify certain elements with certain textiles and its important they know the origin of the textile. With marrying two techniques, one loses the traditional identity a little bit.

“In five years, I would like Amba can be run by Wasim Ansari, who is a second generation weaver and running our workshop in Maheshwar. I hope that he will be able to interact directly with designers and buyers. This will give us more time to work on other weaving cluster development projects and our social welfare projects. I would like Amba to be an example of a fine weaving atelier.” says Hema.