Materials and World Trade | Then and Now

India, the great supplier

Textiles have been intertwined with the advancement of human civilization and everyday living for ages. From sacred rituals and surface decoration to daily attire – their usage has been widespread. Textiles and spices were the primary commodities forming part of international commerce in the pre-industrial period. In those days, India was renowned for its textile quality and efficient trade practices with Far and Southeast Asia. The unique status acquired by Indian textiles is evident in the fact that many words like calico, pajama, gingham, dungaree, chintz, and khaki entered the English language.

The 17th century saw Indienne-prints being carried on caravan routes through Persia and Turkey, onto the ships of sea merchants who facilitated the popularity of such prints in Marseille - an old French seaport, which eventually became the cradle of Indienne and piqué fabrics well before the first half of the 18th century. In the 20th century, with the onset of the British Raj, Indian clothing started to witness a striking English influence that surfaced initially in the upper class and later touched the masses. Throughout history, textiles have served as key symbols of wealth and power and also, as a medium of asserting one’s identity by diverse ethnic groups. Photographs of royals wearing elaborate garments in royal courts highlight the extent of painstaking detail, manpower, time, and money that must have been involved in their production.

Preserving historical remnants in museums has enabled understanding of textile history from a multidimensional lens – the material culture that prevailed - comprising motifs, floral patterns, intelligent color palettes, forms of weaves, environmentally-conscious sourcing, and other aspects. Patronage of artisans and willingness to experiment with new techniques helped lay the foundation of craftsmanship, early on.

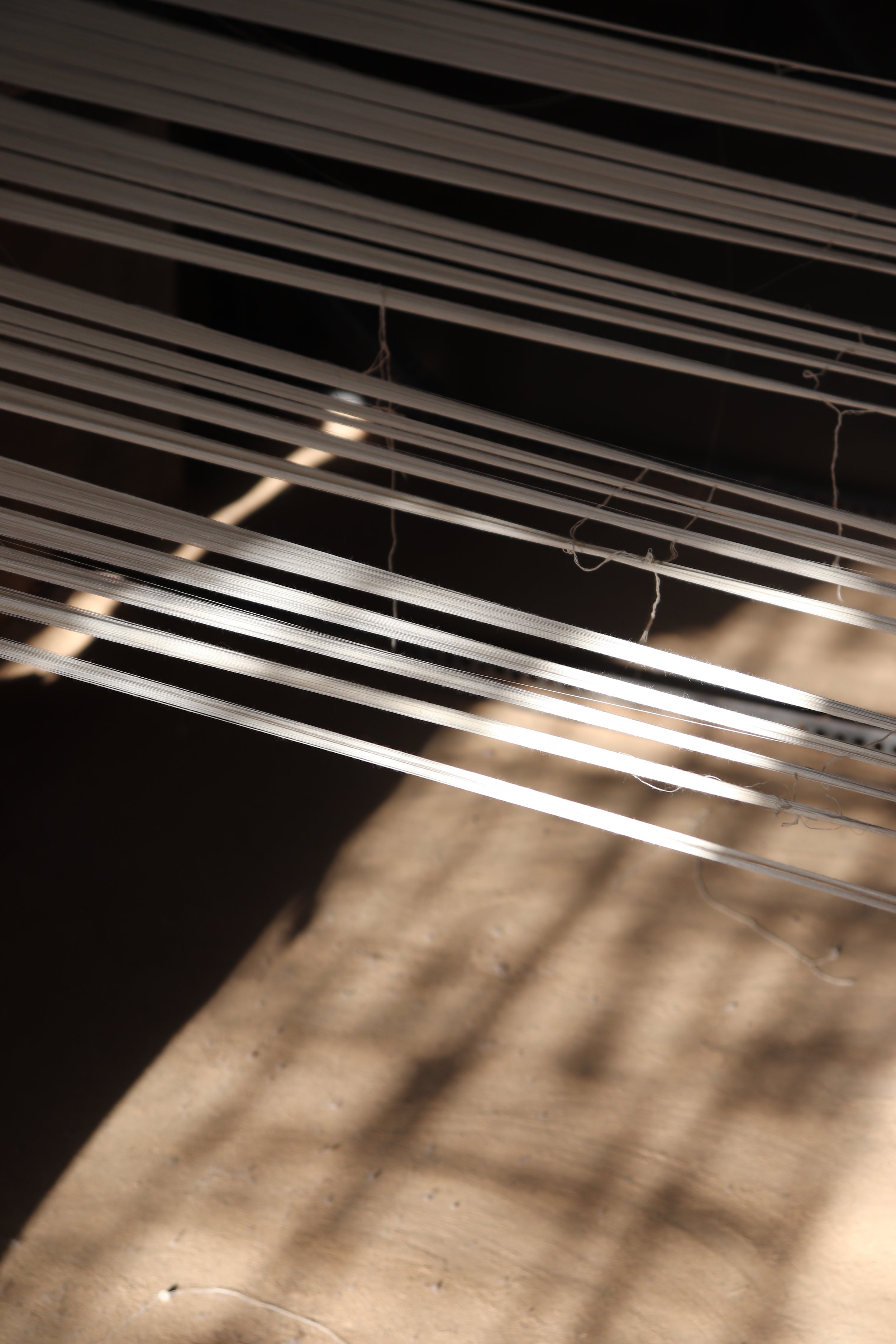

Across India, a rich variety of textiles like Banarasi silk sarees & brocades, Paithani sarees and mashru textiles from Aurangabad, Pashmina shawls from Kashmir, the Bengali Tant saree, and the humble khadi have evolved and are celebrated globally. Their creation has been determined by local climatic, social, economic, and cultural factors and they are vivid manifestations of laborious mechanisms, learned and perfected over time by skilled kaarigars (craftsmen). They make for precious heirlooms and personal wardrobe ensembles while acting as forms of expressing love and admiration during festivities, and crucial life events.

In addition to these, many other forms of textiles have managed to survive the test of time. Ajrakh, a traditional block-printed cloth from the Sindh province of modern-day Pakistan, whose origins can be traced back to the period of the Indus Valley Civilization, is recognized for its complex production methods by design connoisseurs, along with forms of embroidery like Lucknow’s Chikankari and Punjab’s Phulkari. The democratic nature of such textiles, the popularity of e-commerce, and recent proponents of sustainable fashion have helped bridge gaps between artisans and buyers.

Post globalization, India has managed to sustain its dominant position as a textile powerhouse in the burgeoning economy. Being the world’s 6th largest exporter, it holds a 4% share in the global trade in textiles and apparel. Its textile industry is highly superior, with an enormous raw material base and manufacturing strength across the value chain. Its core strengths lie in the hand-woven sector and the capital-intensive mill sector (the second largest in the world). Traditional sectors like handloom, handicrafts and small-scale power loom units have been successful in providing massive direct and indirect employment to people in rural and semi-urban areas, specifically women.

As the world recovers from the aftereffects of the Covid-19 pandemic, international buyers are eager on exploring new sourcing possibilities as alternatives to China. Critical stakeholders in the industry have attempted to embrace incoming trends, both at micro and macro scales. Some of these include mitigating the impact of global warming, understanding, and adopting concepts concerning sustainable fashion, regenerative fashion, and conscious consumption that constitute the Circular Economy. Among design trends, there is an intriguing amalgamation of minimalist studio practices that are working with breezy fabrics and subtle color palettes while focusing on the millennial generation that is adventurous yet seeks comfort and quality, along with brands that have acknowledged the visual and material richness of our design heritage and others, that are bold and vibrant in their outlook. These are the ones that have been breaking stereotypes and have fostered cross-country influences in their design portfolios intending to evolve a maximalist style.

“Every person is the right person to act. Every moment is the right moment to begin.”

– Jonathan Schell

Conscious Consumption

Today, we find ourselves amid a critical juncture when terms like ‘Conscious Consumption’, ‘Sustainability’, ‘Circular Economy’, and ‘Slow Fashion’ are frequently contested, and often reduced to buzzwords and social media hashtags. Given the colossal amount of resources exploited by humans in the name of progress, we must reflect upon the aforementioned concepts with greater depth and foresight. As economic development is happening at a breakneck speed, we ought to be mindful of the time and resources left with us to secure the sustenance of future generations.

One way of achieving this is to travel to the past and sift through historical objects and archives that could take us into old workshops of indigenous communities and help us familiarize ourselves with their craft, design, and textile practices that had evolved in harmony with nature. Identifying their raw materials, weaves, motifs, printing and dyeing patterns, and understanding their relevance in today’s machine-dominated era can enable us to bring macro-level impact by triggering changes at the micro-level. While we tend to place such people in present-day context into the ‘marginalized’ category due to their dwindling socio-economic conditions, it is in reality, these groups who have inherited the secrets to environmentally sensitive production and have long remained central to resource-optimization in their respective practices. We could not acknowledge them early on but with the advent of media, technology, and emphasis placed on new modes of branding and communication, this scenario is gradually changing.

In the past few decades, the realization of the urgency to work toward Sustainable Development Goals has been concurrent with the fact that many textile and craft practices have inundated the market with the intent of creating a positive impact on the environment. ‘Good Earth’, a leading design house globally known for revitalizing authentic Indian craft in luxury design, has been one of the early participants in doing this. On the other hand, many researchers, corporates, social welfare foundations, and resource centers have also attempted to intervene comprehensively in some culturally rich areas and artisans’ communities for addressing sustainability, in turn helping them build a sense of agency in their lives (mostly rural and semi-urban population, particularly women).

For instance, ‘Aadyam’, the CSR initiative launched by the Aditya Birla Group works currently with three weaver communities in India, in Varanasi, Pochampally & Bhuj, aiming to create a self-sustaining ecosystem for the finest artisans by supporting & selling their crafts and impacting their quality of life. ‘Antaran’, the craft-based livelihood program run by Tata Trusts seeks to strengthen craft ecosystems, by building the core strength of handloom textiles such as natural fibers, hand-spun yarn, and natural dyes, while reviving and reinterpreting the traditional weave designs in these selected clusters for wider markets. They have trained artisans in a way that they feel empowered toward entrepreneurship and self-employment. ‘Khamir’, a non-profit platform for the strengthening and promotion of crafts, heritage, and cultural ecology of the Kachchh region of Gujarat, has been serving as a key space for engagement and development of Kachchh's rich creative industries. ‘Obeetee’, an old and prominent handwoven rug company based in Uttar Pradesh, designs carpets that can last for generations while making use of natural and azo-free dyes as part of their design process wherein water is recycled to dye the yarns, and effluents are treated to use for irrigation. Another large rug-making business - ‘Jaipur Rugs’, has been successful in cultivating economic and humanitarian benefits for everyone in its network. Its rugs can be traced back to the original artisans who wove them, and have paved their way into more than 60 countries, in places like Milan, Paris, Beijing, and Moscow.

These are just some of the networks and practices that have welcomed the concept of sustainability with great vigor and conceptual clarity through their nuanced working models while sustaining the timelessness and exquisiteness of the products made. Not only do they command great value and attention globally, but they also demonstrate how studies and preservation initiatives in visual and material culture by entrepreneurs, textile historians & design, and cultural connoisseurs alike, can lead us onto intriguing trajectories while integrating sustainability.

But for anyone to participate in this new ecosystem as a ‘conscious consumer’, there ought to be a growing awareness about what is truly ethical, organic, and sustainable. This legibility can be acquired if one keeps an eye out for certain basic qualities at the time of purchase as ‘Conscious Consumption’ concerning textiles and crafts encompasses a host of principles. These include valuing craftsmanship and artisans as equals, placing them at the core of one’s ethos, paying them fair wages, and responsible sourcing. Recognizing irregularity as the identifying trait of handmade products, altering brand statements that claim to be ‘ethical’, building familiarity with the living and working conditions of artisans’ communities before embarking on senseless production, and experimenting with designs & crafts are also some basic recommendations under this incremental framework. One should also question the promises made by brands in the name of being ‘ethical’, ‘sustainable’, and ‘organic’ and encourage collaborations between studios working on revival and innovation, in an increasingly cluttered market.

Striking the right balance and appreciating both machines and hands for their distinct virtues and functions, fostering networks with karigars as potential entrepreneurs, eliminating gender discrimination, organizing healthcare & educational facilities, and facilitating easy banking are all part of this intricately layered, humane agenda. In our daily routines, our ways of buying, sourcing, producing, packaging, delivering, using, and reusing can all be re-aligned with this ever-expanding set of practices. Our patterns of consumption and waste management are all intertwined together and it is a matter of our willingness to pause and reflect on these, which shall determine how we contribute to the circular economy - one that stresses reuse, renewability, and durability. In recent times, it has become quite evident how the power of research and efficient communication, when utilized in the right direction can help trigger change across many aspects of the value chain. However, what is imperative is the elimination of misleading notions that surround this discourse like how the terms ‘contemporary’ and ‘modern’ have been often been overused or misused whereas in reality, tend to lack specificity.

Homegrown labels like Rina Singh’s ‘EKA Design Studio’, Sanjay Garg’s ‘Raw Mango’, Atelier Ashiesh Shah, Indigene, and B Label constitute an eclectic mix of practices that have surfaced recently and have brought in a new kind of consumer – one who is keen on knowing about the products being purchased and the environmental, cultural, and socio-economic repercussions involved in doing so. Many of these studios have been both enterprising and experimental in terms of working with minimalist and maximalist styles that have consequently led to a whole new form of visual, material, and cultural expression. While integrating artisanal characteristics and retailing globally, they have managed to communicate their vision and stories through meticulously curated visual campaigns on social media platforms, thus building a bridge that needs to be walked on carefully.

For the environment, there’s no possibility of recourse as the damage caused can never be undone. But what can be learned are ways of negotiating between the ‘fine’ and the ‘fractured’ & the ‘obvious’ and the ‘uncertain’. Since we are headed towards a shared future, it is better to part with conventional molds, show empathy towards artisans, align our thoughts regarding conscious consumption with one another, and watch them manifest in our practices in due course of time. These manifestations however will remain contested as our social and economic structures continue to be heavily influenced by capitalism, reward-seeking, and factors that might be invisible to the human eye. Cultural consciousness alone, cannot be adequate for bringing inclusive, sustainable outcomes. It exists within a large, complex nexus of individuals and groups. Thus, the idea of sustainability can perhaps never be fully comprehended, strategized over, or achieved with an equal amount of clarity wherever a large number of stakeholders are involved – each armed with its unique purpose and varying notions of development.

Images 1 & 2 - By Sayali Goyal

Images 3 & 4- Obeetee Rugs