Symbolism

“All art is at once surface and symbol. - Oscar Wilde”

INDIA TO MEXICO

The term ‘symbolism’ traces its origin from the poetry of Charles Baudelaire, prominently his Les Fleurs du mal. As a literary movement, it flourished in late 19th century Europe and was soon incorporated in painting, architecture, and other mediums. As an art movement, it followed a distinct pathway and revived a romantic tradition rooted in mysticism, metaphors, and mythology. The European symbolic art movement emerged as an interesting interplay between ambiguity and intuitions, imagery and metaphors.A Eurocentric definition of symbolism in art, however, will be an oversimplified and facile venture.

To the dedicated aesthete, the kernel of symbolism goes beyond its modern manifestations and digs deep into the hidden roots of ancient civilizations. The history of symbolism as an art, craft, and design concept can be discovered through the myriad histories of human civilization, indigenous socio-cultural practices, and pre-colonial knowledge systems.

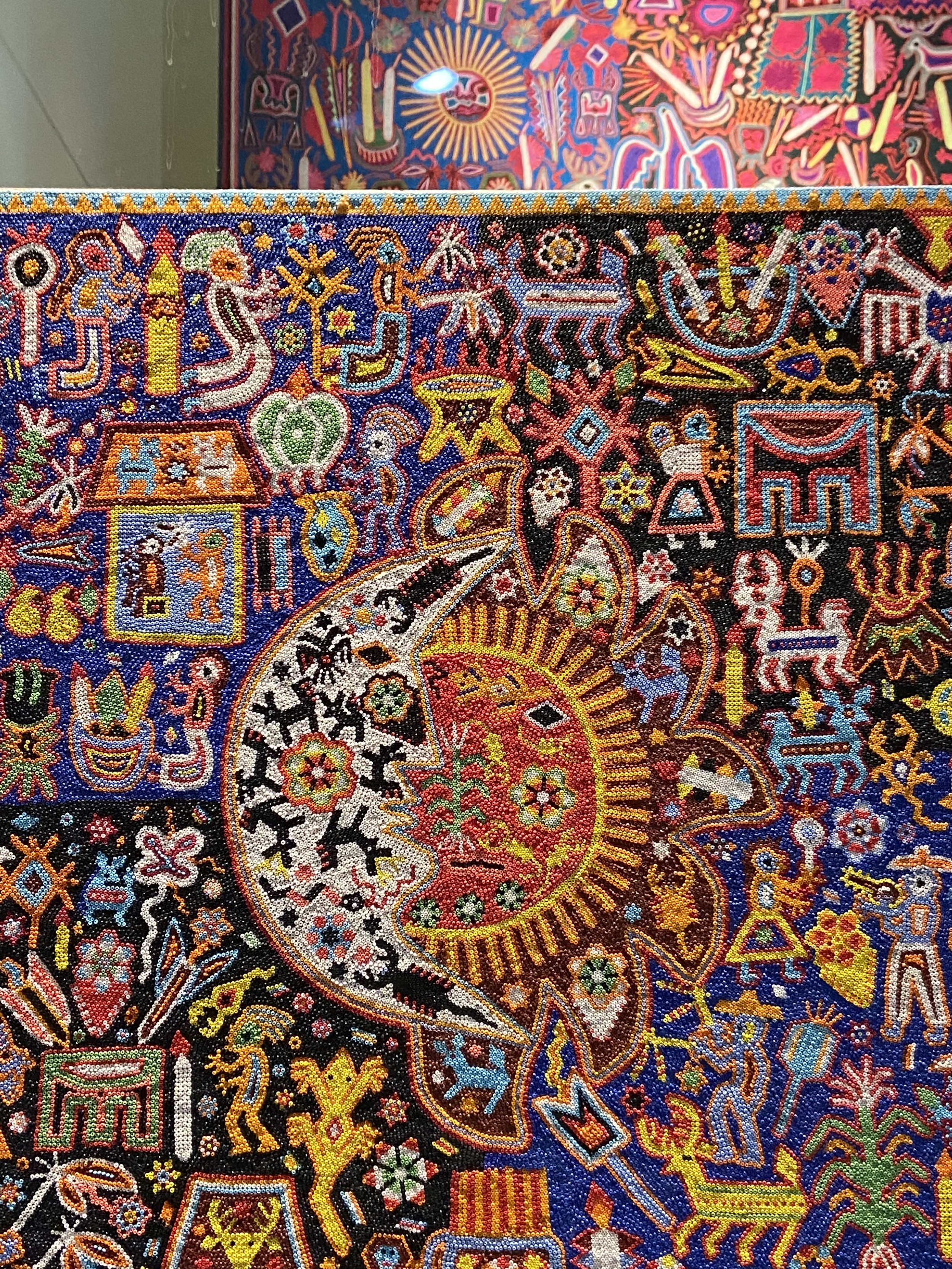

Symbolism’s primary expressions appear in the old world societies as a tryst with wonder about the cosmos. The sun and the moon play a crucial role in the symbolic iconographies of three primeval artisanal regions: Mexico, Morocco, and India. The pyramids of the sun and moon in Mexico exemplify symbolism through architecture. The shams wa qamar or a sun-and-moon bracelet is a unique rendition of celestial bodies in the form of jewellery in Morocco. The cosmic energies of the sun and moon are represented as deities and worshipped in India.

As cradles of symbolism, these lands are steeped in symbols. The Amazigh people of Morocco etch symbols on their skin through tattoos as talisman and markers of identity. The Mexican communities weave symbolic patterns on their fabric and natural motifs on rugs, enhanced with the warm colours of natural dyes. The ancient tantric practices of India employ yantra or esoteric diagrams denoting symbolic powers. The merging of an upward triangle and a downward triangle represents creation, the union of masculine and feminine energies. Vastu and Rangoli embody the symbols of colours and elements within the walls and on the floors of Indian households. A symbol can represent an idea, an identity, a practice, or a philosophy. It acts as the mirror of the unseen and a language for the community.

A journey to understand symbols leads to interpreting and reinterpreting religious beliefs along with its art. Symbols are sometimes bound within the confines of the supernatural - exemplified in the Mayan and Aztec symbols of Mexico, the Berber and Islamic symbols of Morocco, and the Aryan and Dravidian symbols of India. In Mexico, Morocco, and India, symbols are codified and universalized but also fluid and evolving. The practical acceptability of symbols in crafts, art, architecture, and design reflects a vital epistemological characteristic unique to these places. The importance of symbolism is emphasized as part of their daily lives and practical utilities.

This issue probes an anthropological query into symbolism in art through the Mexico-Morocco-India triad of indigenous cultures. How are symbols related to everyday lives? Why are symbols used to represent an ideal? This issue aims to study and appreciate the socio-cultural character of symbolism in the fabric of human lives and knowledge.Today, when every concept and practice is seen under the lens of post-colonialism and ecological consciousness, readers can delve into the rich traditions and roving tales of arts and antiques in these lands that embody the spirit of symbolism.

IN MOROCCO

The visual horizons of Morocco are a stunning combination of colours and patterns. Morocco brings to mind night markets, woven baskets, delightful tapestries, and rows of colourful houses standing scintillating beneath the desert sun. Craft has a prominent place in the local culture of Morocco. The influence of Islamic art and geometry are hard to miss in their cultural landscape. Symbols and signs are abundantly found in pottery, textiles, carved or painted wood, leather works, jewellery, amulets, and tattoos, reminding us that long before the script was a form of communication, art and symbols helped humankind express themselves.

Symbols on the Skin

Tattoos are a part of many indigenous and ethnic cultures around the world. Recognised as a form of body art carrying deep anthropological significance, they convey meanings, identities, and often the unique journey of an individual. In traditional communities, they also communicated the social status of the individual or the rite of passage into a certain stage of life and society. The blood and ink mixed together created body art in what must have been sacred rituals to etch scripts and symbols.

The Amazigh, also called the Berber community, who lived in scattered dwellings amidst the mountains, tell a similar story. A major ethnic group in Morocco, the Berbers possess a rich artisanal heritage and knowledge of producing cultural artefacts. For centuries women of the community have proudly adorned their skin with stunning jewellery designed with tribal symbols as a marker of their identity. They believed that these signs and symbols carry magical attributes that guard them against misfortune and evil eyes.

(Moroccan folklore is no less rich in symbols!) Jewellery also served as markers of wealth; the more tattoos a woman had, the wealthier she was. These tattoos often were a series of dots, fairly simple decorations, straight line features, twisted lines, V-shaped motifs, curves, cross lines, geometric shapes in squares, circles, triangles, and plant and animal forms. Nowadays, henna tattoos have replaced permanent tattoos.

Women and craft

Women are the face of art and craft in the Berber community. Carpets, clothing, ceramics, tattoos, jewellery, and other forms of handmade culture distinguish the community from others and contribute to their vibrant heritage of symbols and rituals and handcrafted objects. All created by women. For the weavers, wool is considered sacred, and the journey from wool to a rug is seen as that of a living soul – just like human life. That is why the whole process of weaving involves many rituals. People believe that there is a lot that could go wrong; for example, the loom can collapse or the yarn can break. Therefore, when setting up the loom, sugar is broken and dates are eaten, to ensure that the process of weaving becomes favourable. Also, when a rug is completed, no one steps on it with their shoes on. The crafted piece is given a lot of attention and care.

It is fact well documented across the world that women-centric craft processes have produced repertoire such as folk songs, rhymes, and limericks that helped them beat the fatigue of exhaustive labour and long hours of work. These organic expressions of work and female bonding are narratives that provide us with a useful peek into how they performed such work as a community.

Craft today

Before the rise of commercial trade, carpets were mainly crafted for personal use. The unique story of the collective consciousness of Berber women lives on in these textiles. The popularity of Berber carpets has grown enormously and with good reason. They fit into any interior, from modern and minimalist to classic and rural. The rugs are made from the wool of their herd. The wool is dyed with colours derived from plant and mineral sources found locally – such as pomegranate, henna, and roots of the walnut tree. There are a great variety of these rugs depending on the tribe that weaves them. It goes without saying that each rug is unique and an authentic piece of folk art.

The Berber signs and motifs on bodies and crafts alike represent an accumulation of ethical and social norms. They all carry rich ideas, philosophies of life, death, work, hope, family, nature, and more. This craftsmanship is getting lost like an ancient language but it remains one of the most authentic age-old traditions that must be carried forward. And they continue to enrich the living traditions and material cultures of the region.

Illustration by Gayatri Menon