In Conversation with Neeru and Namrata Kumar

You seem to work with certain material, how did you settle on it and what possibilities were you able to explore with it?

In terms of materials, very early on I was excited by the possibilities of tussar silk. I made a visit to Raighad and Champa, in the tribal area of Chhattisgarh state, the hub of wild tussar silk production. The natural colour, texture and lustre of tussar captivated me. I felt this was a yarn with immense possibilities, and perhaps could be combined with other materials like wool, linen and cotton. I tried out different weaves and after a lot of experimentation I eventually developed a new vocabulary which seemed to convey my aesthetic. The first textile that I produced using tussar, called appropriately, ‘The First Design’, was an enormous success, exhibited at the Festival of India, and later produced to countless orders. The First Design has been described as A Classic of the Future, and indeed continues to be demanded in large volume, despite the many copies and look-alikes that were since generated! There has been a constant process of development since the early 1990s and textiles for the home and apparel have also been well received. The aesthetic seems to appeal to a niche international community that has an understanding of textiles, whether in Japan or in the United States. In Europe, France and Italy are the largest markets for these tussar-based textiles.

How did you further develop your work? What new technique were you able to incorporate?

“One cannot rush the handmade. The slow process of creating textiles has been for me an artistic journey. I feel that textiles are something we embrace every day, something that is an intimate part our culture. I would define textiles as an art of the everyday.”

The sophisticated ikat weaving tradition of Odisha was a favourite technique I explored. I was able to convince a weaver to work in my studio in Delhi and designed saris using his incredible skills and those of his family who contributed to the elaborate process. While employing this traditional technique my effort was to get away from the traditional designs, from the usual codes and motifs, and create something that was fresh and new and now! The experiment was a success. I did a whole series of Orissa saris which were much appreciated.

The Kantha quilted embroidery from Bengal was another fascinating tradition. This embroidery technique allowed me to give a new lease of life to vintage textiles. Exquisite new textiles were also created which had their own, very contemporary, identity. During my work with Kantha artisans I chanced upon fabulous pieces of Kantha quilts which the women in the villages of Bengal made for their daughters as part of their dowry. The textiles were showcased to customers in Europe and the USA and were much appreciated. The spread of awareness of the Kantha quilting tradition has generated an immense amount of work and income for the women quilters in Bengal, sustaining livelihoods while keeping the tradition alive.

The development of Khadi, the hand spun and handwoven fabric of India, has been an important part of my work. In the late nineties a lot of effort was invested to create Khadi fabrics that could be used for clothing. Various weights of Khadi were explored in new colours and textures to make clothing that was practical and comfortable.

Our wonderful textile traditions seem vulnerable in the world of mechanized production and fast fashion. But there is hope due to a renewed interest worldwide in the handmade, its timeless beauty, its tactile nature. One cannot rush the handmade. The slow process of creating textiles has been for me an artistic journey. I feel that textiles are something we embrace every day, something that is an intimate part our culture. I would define textiles as an art of the everyday.

You have a unique sense of colour and composition. How do you use that to set the mood for the artwork?

“I really believe that art should be an interpretation of what one sees, rather than being an absolute imitation of reality.”

Post my graduation, I worked for a number of years in the field of graphic design and illustration across different design studios in New Delhi. After almost 6-7 years of working, I started freelancing, taking up mostly graphic design related work. Then, around 3 years back, one fine evening, inspired by a young artist’s work, I began to paint portraits and just like that, very organically, I began my journey as a painter. One of the very first series that I painted, which remains extremely popular with my audiences to this day, was the series ‘Women of Ceylon’. Colour played a very important role, I used a limited palette of deep emerald green, aubergine purple, mauve, ivory and gold in this series. Colours have the ability to communicate, and when certain colours are used together, they are able to evoke a mood and set a vibe. I generally try and use a limited colour palette for each series, I feel this helps to make the tone of series stronger. For example, the ‘Seated Women’ series has a colour palette of deep, rich shades of magenta, green, mauve, turquoise, scarlet, gold and brown which gives the paintings a vivid yet old-world feel. Choosing the right colours is a crucial step as they set the mood of the artwork, so I definitely take time and try to be thoughtful with this step.

What were your source of inspiration? what is your thought process?

“The exciting things about art is that it has the power to provoke the imagination, to carry the viewer to another world temporarily, and to allow one to experience the world through someone else’s perspective.”

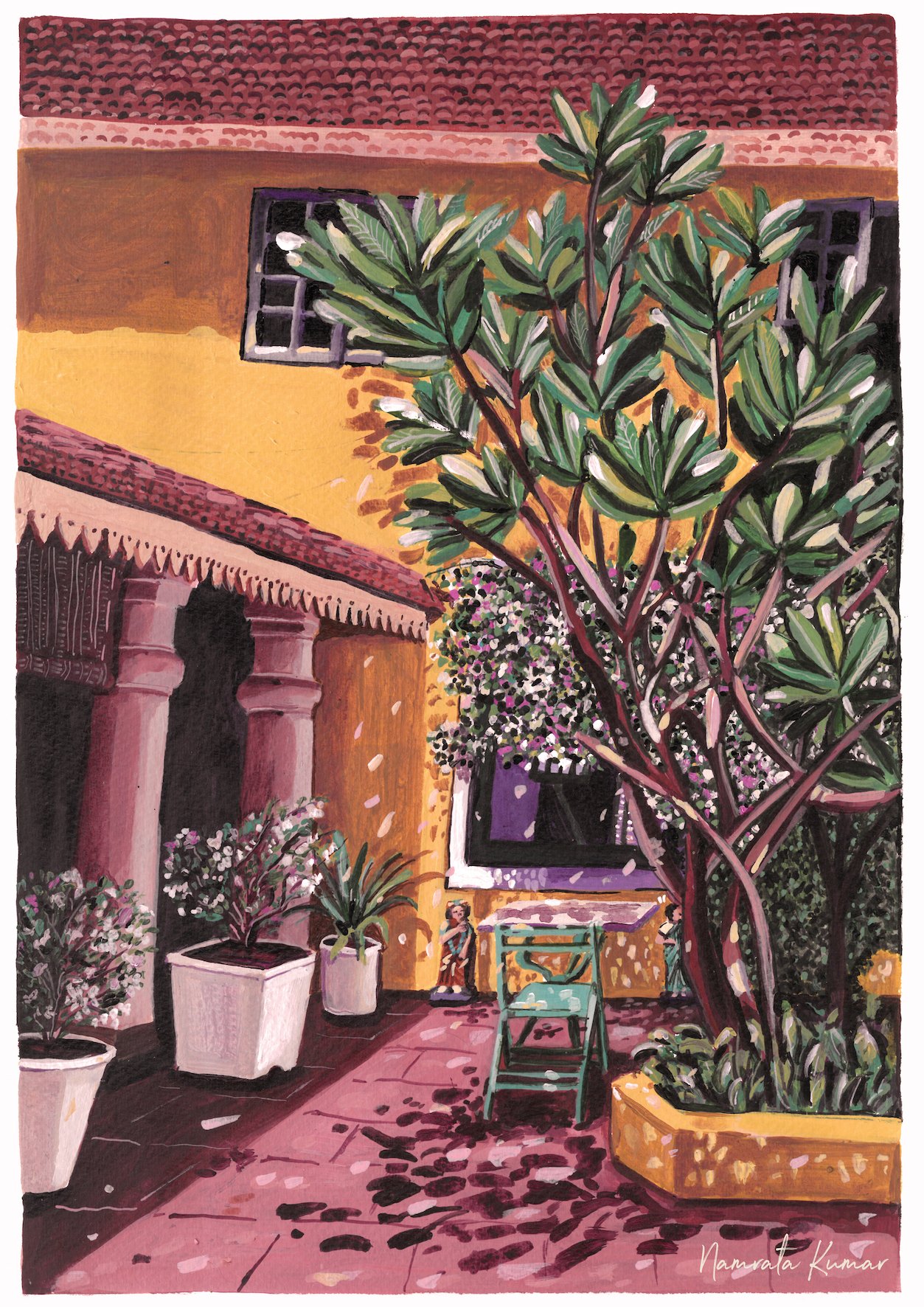

I’m really inspired by places, people and culture. I love to travel and when I visit new places, I like to soak in my environment and understand what gives the place its unique personality. When I paint subjects such as Seascapes of Kutch, and buildings of Fort Kochi, I try to capture the essence of that place and evoke its spirit through my artworks. For example, because the artworks in the Seascapes of Kutch series are painted in a really muted colour palette and have minimal compositions containing very few elements, they evoke a certain stillness, and have an almost meditative atmosphere to them. The artworks in the Fort Cochin series have been painted in a rustic colour palette of cerulean, ochre, rust and teal, with slightly distressed brush strokes, resulting in the viewer being transported to the artistic streets of Cochin, dotted with beautiful old buildings. The exciting things about art is that it has the power to provoke the imagination, to carry the viewer to another world temporarily, and to allow one to experience the world through someone else’s perspective.

Researching artists has led me to important sources of inspiration for me. Over the past year or so, I rediscovered the work of the French art Henri Matisse, and through him, I stumbled upon the Fauvist art movement. The work and style of les Fauves (French for "the wild beasts"), a group of early 20th-century modern artists whose spontaneous response to nature was expressed in bold, undisguised brushstrokes and high-keyed, vibrant colors, really resonated with me. I am finding myself over time, more and more attracted to the use of vivid colours, and abstracted forms that are more expressive than representational. I also find myself drawn to the subjects chosen by the fauves, paintings of room interiors as well as abstract landscapes. Matisse in particular has been a huge influence, I love the use of textiles and colour in his paintings.

What I love most about Fauvism is the instinctive, visceral quality of forms and colour. I really believe that art should be an interpretation of what one sees, rather than being an absolute imitation of reality. Art can almost be thought of as a personal language – the works of Klee, Kandinsky, Andre Derrain, Raoul Dufy, Picasso, Matisse, Calder - the list goes on, are all examples of the artist expressing what they see using a combination of instinct and intelligence. Intuition and instinct play a colossal role in creating new perspectives, and re-inventing the wheel, which I feel is a crucial role of the artist.

You have engaged in interesting collaborations with textile/ design brands too. What was your experience like?

My very first collaboration with a design brand was with Nicobar. I worked with Nicobar in 2019 when they were launching their collection ‘Midnight Wonderland’. I was invited to one of their shoots, where they were working with photographer Tarun Khiwal to create mood shots. The idea was to allow me to soak it all in, and then interpret the collection in the form of artworks. I then proceeded to create six digital paintings for them, which they then launched on their social media channels. This collaboration brought immediate attention to my work, and I overnight gained an Instagram following that has steadily been growing. I have since collaborated with Pero, House of Angadi and Ritu Kumar, all textile led fashion brands, to create paintings for their collections. The reason that I’ve truly enjoyed working with these brands is that, because they are design houses, they gave me a lot of creative freedom and really allowed me to interpret their work the way I chose fit.

ALL PHOTOS / NEERU AND NAMRATA KUMAR

When I think of Indian contemporary textiles, I think of Neeru Kumar’s contribution since the 1990s. An Indian designer who has experimented with traditional weaving and surface techniques like ikat, tussar and shibori (to name a few) to create globally relevant versatile silhouettes, Neeru Kumar continues to innovate within textile experimentations in fashion and home. Interestingly, I had been following Namrata Kumar’s work that explore silhouettes, Indian interiors and portraits in warm acrylic and oil colours, and had to interview the creative mother- daughter duo. They speak about their journeys, process and cultural influences.

WITH NEERU KUMAR

How did you get into textiles? Could you walk us through your journey?

As far back as I can remember, I have been drawn to textiles - to their colours, textures, design. This was probably influenced by my surroundings for I grew up in Ahmedabad, a city with a long textile history and a rich legacy of textiles, vintage and modern, found in the many cloth shops dotted all over the old city. I also have distinct memories of childhood that relate to the clothes I wore. Even when very young I had strong likes and dislikes. Colour and texture were very important. Somehow the rest of the family started to recognise and respect my aesthetic and soon my approval was sought for any textile or article of clothing that was bought by anyone in the family!

A chance visit to NID in Ahmedabad defined my destiny. The moment I saw the sample loom in the textile studio I knew weaving was my calling. My years at NID opened up for me the whole world of textile traditions. I learnt about the wealth and variety of textile techniques in India, as well as the textile traditions of other countries and cultures. I discovered that I was attracted much more to textiles that had a certain graphic and textural quality, whether the textiles of the Bauhaus Greats - Gunta Stozl and Anni Albers - or certain traditions in African and Japanese textiles.

What is your take on various cultural influence on Indian textiles and vice versa?

“I see textiles not as static objects but as a living, breathing, medium with a depth of cultural significance.”

Early on in my career, along with the geometries of the Bauhaus, I was intrigued by the widespread influence of Indian textiles in south-east Asia all the way to Japan where the love for Indian textiles was combined with a sense of abstraction. My experience in Japan helped me to look at our own textile history outside of its academic confines. I was able to work with textiles in a more fluid, creative and artistic way. I never self-consciously created textiles as a form of art to begin with, but over time I began to see textiles as a liberative form of artistic expression beyond any reductive limits.

Working with a range of textile artisans enriches and influences my own practice. One also realises that working with textiles comes with a sense of responsibility. Textiles carry history, skills handed down over generations, the role of patronage, cross-cultural influences, and so on. As you try to capture some of its history, you realise that you have become a bit of a collector and an archivist and you begin to see the cultural power that textiles wield. I see textiles not as static objects but as a living, breathing, medium with a depth of cultural significance.

With a detailed knowledge of Indian textiles and techniques gathered over several decades, I continue to learn new things. That curiosity energises me and my brand. I feel my brand will continue to evolve as we come full circle to questions of sustainability and fair-trade that were embedded in our consciousness all along. There is still a lot to explore which is very exciting.

WITH NAMRATA KUMAR

When did your artistic journey start? Where did you interest lay?

I’m from a family where art and design is almost a way of life. Being born to a textile designer, art and aesthetics seeped into my life from a very early age. As a child, I loved drawing, painting and craft activities, I particularly enjoyed making things with papier Mache and clay. I have memories of tearing up and soaking newspaper and making paste out of ‘atta’ and water, which was then combined with the newspaper to make papier mache. I would create things ranging from bowls and plates to jewellery would then paint them intricately. I still, to this day, use some of these objects that I made as a young child.

What pushed me further down the artistic path, without me even knowing it, was watching my mother work. My childhood was unique, I would accompany my mother to the weaving looms and dying units, and watch as she would work with the weavers, discussing material, colour and pattern. Ever since I can remember, there were always dealers selling vintage textiles from different parts of the country, all the way from Kutch to Kullu. At that young age, I was not artistically evolved enough to appreciate the value of such wares, however, without even realising it, I was slowing internalising and imbibing all that I saw.

In the traditional sense, the style you portray is different and unique, could you elaborate about you finding your creative self?

I studied fine art for 4 years as a major in school from class 9-12. It was in this class where I was first taught how to use my pencil in a skilful manner. Many still lives and nature studies later, I was slowly getting accustomed to pencil and paint.

After school I went on to attend a design college called the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, based out of Bangalore, India. The first two years were foundation studies where we were exposed to the basics of art and design. We were taught fundamentals about mediums, essential techniques and also encouraged to make creative decisions. Two years into my degree, I chose Visual Communication Design as my specialisation. Here we were taught typography, layout, colour and concepts such as hierarchy, balance, rhythm, and symmetry, among others. We were introduced to illustration, and the ways that it can be incorporated intelligently into design. After receiving formal training, I found myself intrigued by this particular aspect of graphic design and tried to include it as far as possible in my work. My final thesis project was an illustrated game for children. The game encouraged children to think creatively by coming up with unique stories based on methods taught by the design thinker Edward De Bono.

The great thing about Srishti was that it was a young school, and therefore, still experimenting with finding its identity. The creative freedom allowed to the students was incredible, and no idea was considered too outlandish. A crucial introduction to the world of design thinking was given by faculty member Poonam Bir Kasturi, a graduate of the National Institute of Design. The course she taught was aptly named ‘Unlearning’ and as the name suggests, the objective of the course was to unlearn what we thought we knew, to diminish our preconceived notions and adopt a different, more fluid worldview. This was an introduction to lateral thinking, to the concept of there being no correct answer, and to the idea of understanding the problem and finding creative and unique design solutions. Valuable lessons such as learning to respect the integrity of a line and dot, and then learning how to manipulate the line and the dot for effective communication were learnt.

Do you experiment with other mediums? And what style/medium would you like to incorporate into your artwork?

“My work is really about fulfilling a need, rather than being about making a political or social statement or about being purely self-expressive.”

I have recently started painting with oils, and am finding the medium challenging and exhilarating. Oils have a very different temperament to most mediums I have worked with in the past and it will take a fair amount of practise until I feel fully comfortable with them. I intend to devote time to developing a collection that I can eventually exhibit.

Apart from painting, I now find myself at a stage where I am being pulled towards my graphic design roots. While I will continue to paint, I am interested in moving in a direction that marries graphic design, art and textile design. I am interested in the screen printing method, and am interested in creating functional home textiles as well as art using this technique. I also want to explore working with ceramics with a focus on surface design. I consider myself more a designer with an artistic eye rather than an artist in the traditional sense. I view even my paintings as functional objects, designed to liven up spaces and bring joy and pleasure to the viewer. My work is really about fulfilling a need, rather than being about making a political or social statement or about being purely self-expressive. I want to continue down this path, and create artistic functional objects that have my unique stamp on them.