Textile Narratives | Museums and Galleries in London

Textiles are a key component of our material history, the importance of which cannot be understated. They need to be considered holistically; each piece is not only a product, a design, or even a piece of art, but is also a method of passing on a story. On our recent visit to London, C&J visited a range of textile exhibitions to observe the role of textiles in telling stories across the globe.

Textiles as Art

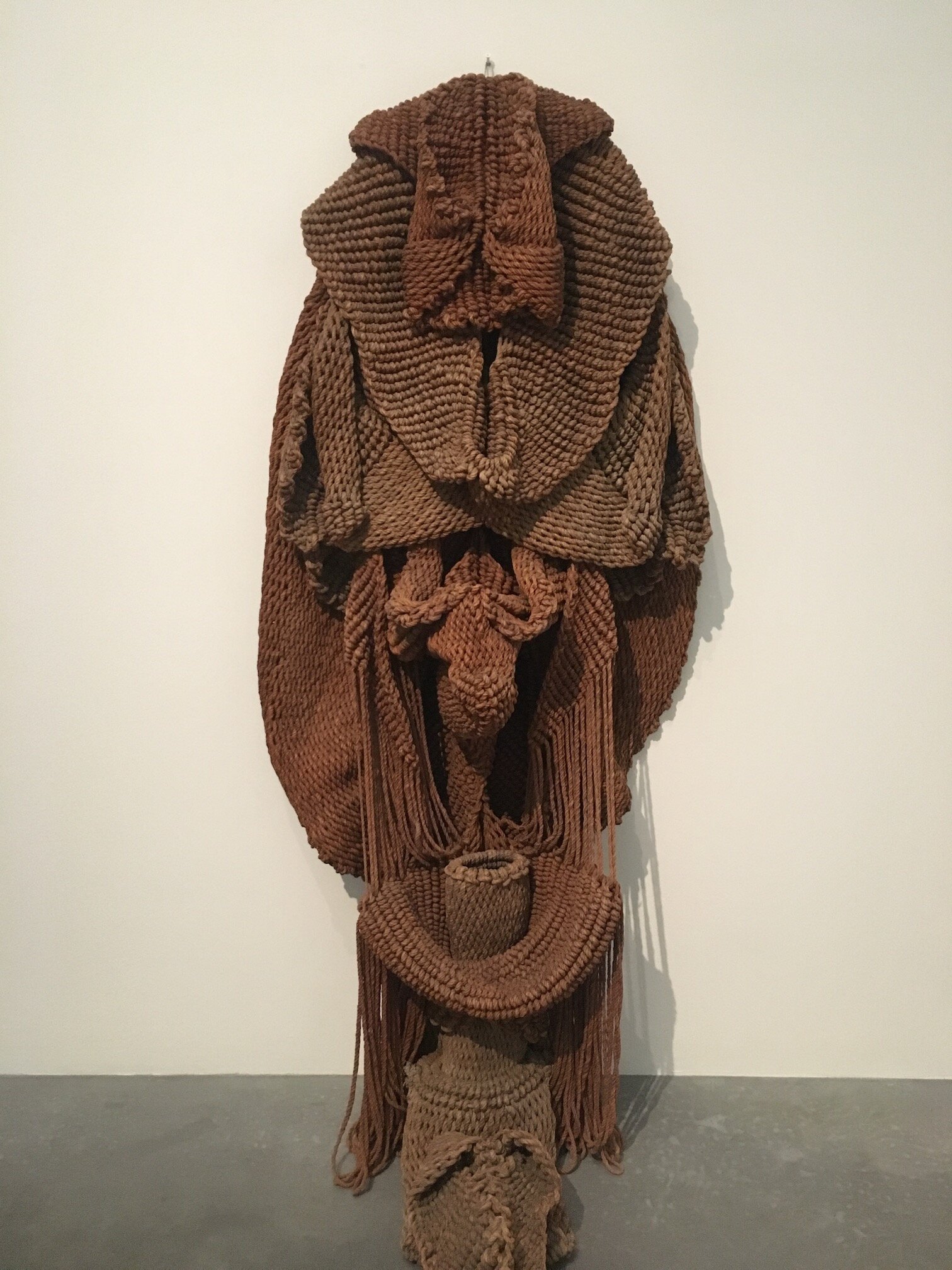

The work of Indian artist Mrinalini Mukherjee, who famously used textile materials to express her art, is being displayed at the Materials and Objects exhibition in the Tate Modern; an exhibition looking at the way artists around the world have used diverse and unusual materials in their work.

Mukherjee’s parents were well-known artists and spending her adolescence in the artistic community of Santiniketan in Bengal, she grew up submerged in debates about modern art. After studying painting, she turned to sculpture but rejected conventional materials and techniques, opting for natural fibers, ceramic and bronze. She worked instinctively, without plans or preparatory sketches, perhaps most famously with hemp rope, of which her two sculptures in the Tate are made. Through weaving and knotting she created complex, life-like structures; her earlier creations names after deities of fertility.

Born immediately after India gained independence from Britain, Mukherjee had to navigate the confusing crossroads between a return to the traditional versus Indian modernism, and what that should look like. Her creation of sculptures by painstakingly knotting hemp rope were firmly rooted to the traditional Indian textile arts, but also display a brave experimentalism. Indeed, she was one of a number of women artists who introduced textiles as important materials to be used in the fine art of sculpture, and in the process, left an incomparable legacy in modern Indian textile art.

Her Tate sculptures, named Jauba in reference to the hibiscus flower, are human-scale structures, constructed of hemp dyed in autumnal colours, together with steel. The sculptures are flower-like forms, but perhaps also have feminine connotations, in stature and impression.

Textiles as Identity

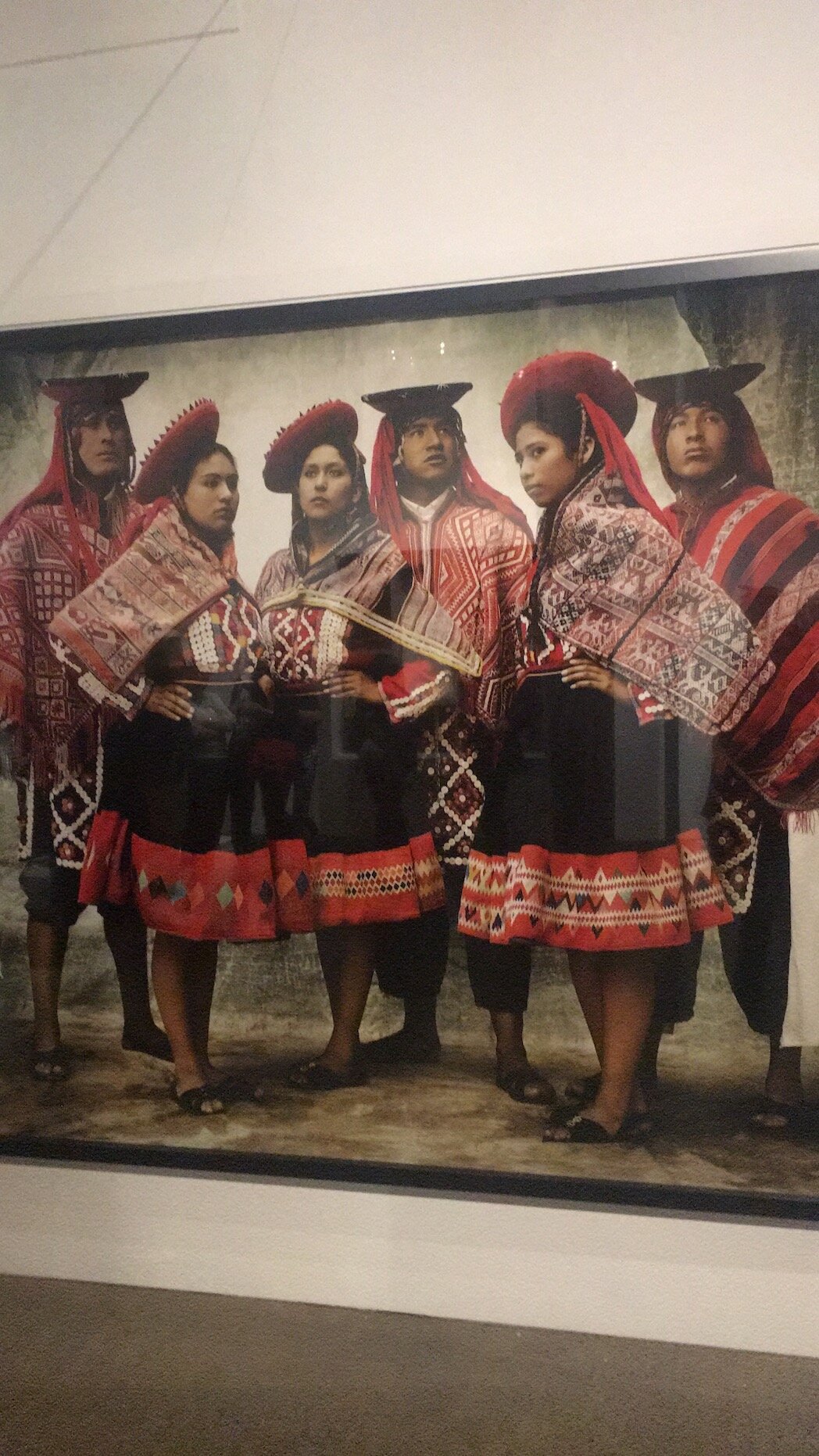

The Weavers of the Clouds exhibition, on display at the independent Fashion and Textiles museum, brings an anthropological aspect of textiles to London in an impressive example of cultural exchange. It tells the story of Peru’s long history with textile art and its importance to the different communities of the country.

Peru’s textile tradition dates back more than 7000 years, with this exhibition containing examples dating as far back as 300BC. Ruled by numerous groups, Peru and its artisans have continually developed their style, but with colour and detail remaining constants. An ancient skill passed down the generations, the use of fibres and fabrics is closely tied to Peru’s economic, social and political history. For example, textiles embody the living history of the highland areas with patterns named after elements of the natural world, such as rivers or mountains, and symbolise the Quechuans’ belief that they live and work in harmony with Pachamama, or Mother Earth.

The dry climate of the coastal burial regions has meant examples of these ancient textiles have been preserved until this day, creating a repository of different materials and styles from which to learn. Each region has its own distinctive designs, with specific patterns or styles differentiating communities and indicating ethnic and social standings. During the rule of the Incas in the 15th and 16th centuries, textiles were considered prized possessions and also status symbols. When the Spanish conquered the Inca empire in 1528, they destroyed all written records of Quechua customs and folk-lore, and indigenous textiles designs remained as the one of the few vehicles for the transfer of cultural information.

In some parts of the Peruvian Highlands, life has remained relatively unchanged for centuries: men farm the land to feed their families and women raise llamas and alpacas which provide the materials for weaving. The exhibition displays the diverse range of techniques employed by Peruvian weavers, including various weaving techniques, tapestry, embroidery and applique. Many of these techniques, which pre-date colonialisation, are still used by local communities throughout Peru today.

In communities such as Chinchero, girls start weaving using traditional backstrap looms from the age of seven. Remote communities such as this are holding out against the homogenisation of societies, preserving their customs and traditional production techniques against the onslaught of globalisation, raising the important question of how to maintain their cultural identity in the changing world.

The second part of the exhibition goes on to describe how indigenous weaving techniques have continued to influence contemporary Peruvian fashion designers, merging the ancient textiles tradition with the present. Several designers are collaborating with local artisans, bringing a valuable source of income to communities. But they are also reviving interest in the historic crafts of the region and creating an alternative to the fast, unsustainable fashion trends that have subsumed the modern world.

Textiles as Beauty

The British designer and craftsman William Morris had a lifelong dream – “to do no less than transform the world with beauty”. Considered one of the most important cultural figures of Victorian Britain, Morris believed beauty was an essential requirement of life and strived to bring art into the everyday through the design and production of textiles. Born in London, in 1834, at a critical juncture of British society, he combined industrial zeal with cultural exchange, hand processes and high-quality materials to embed textiles into Britain’s material history.

Morris was fascinated by textiles, over his life producing items using a range of crafts. After initially adopting embroidery for commercial use, he moved onto dying, block printing and weaving. He accepted his gift was for repeat patterns, and continually threw himself into processes needed to master the technical aspects required to produce his own creations. The William Morris gallery in North London, housed in a building where he once lived, exhibits a range of original pieces, many of these inspired by indigenous flowers and plants of England, a display of his love of natural world.

In textile production, he made extensive contributions, reviving a number of dead techniques. He saw dying fabrics as a natural preliminary to the production of woven and printed textiles of the highest quality, and spent years mastering the process of dying. He disliked the bright blues produced by synthetic dyes and instead focused on using plant-based substances, in particular, indigo. His work experimented in the development of new methods, and resulted in indigo dying being readopted as an industrial practice.

Inspired by Asia, Morris is accredited with bringing the ancient Indian art of block printing to the general public. By the mid-19th century, leading commercial manufacturers had switched to engraved roller printers, one of which could print as much cloth as 20 hand-block printers. However, Morris believed the original Indian block-printing process created a better-quality finish and employed craftsmen to print textiles by hand, using carved woodblocks.

By the 1880s, Morris was a household name and he was supplying furnishings to middle- and upper-class families in Victorian England. He was a key figure responsible for bringing the beauty of textiles into mainstream culture, and even today, his style of work can be seen to have had a lasting impact on the tastes of British society.

Words by Eileen Mcdoughall

Photos by Sayali Goyal