Ladakh Arts and Media Organisation

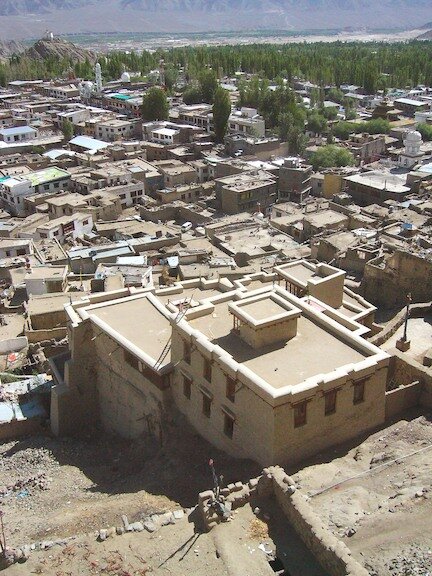

The LAMO, Ladakh Arts and Media Centre is located in the historical old town of Leh, below the 17th century Palace, and dates from the same period. It comprises of two houses – the Munshi House, home to the King’s secretary, and the Gyaoo House, home to court artists. Both homes were not inhabited, the former since 1984 and the latter for about 100 years. They were in a state of decay, many rooms were without roofs and walls below had collapsed. Beams had bent, pillars warped and water penetration had occurred. The external areas were covered in garbage, human and dog waste. This is the case with much of old town, especially the areas below the palace, and though declared an endangered site and included on the World Monuments List in 2008, the area is vulnerable to threats by redevelopment. From 2006 to 2010, the two homes were restored by LAMO and revitalized as an art space with exhibition galleries, offices, library and open-air performance site. The Centre conducts outreach programs, research and documentation projects, workshops, art residencies, performances and exhibitions that showcase Ladakh’s material and visual culture, performing arts and literature. It has become a vibrant space for Ladakhis and visitors to the region and is especially popular with the youth.

We spoke to Monisha Ahmed, co-founder and Executive Director of LAMO, to understand the goals of the organisation:

1. Could you tell me about the inspection of LAMO and the purpose of the initiative?

The Ladakh Arts and Media Organisation (LAMO), was formed in 1996 as a public charitable trust by Monisha Ahmed and Ravina Aggarwal. Both of us have many years of working in Ladakh, as students of anthropology we have done our doctoral degrees there.

In addition to its educational, cultural and social aims, LAMO wanted to identify a heritage building in Leh, conserve it, and establish an arts resource centre within its premises. Alarmed at the neglect of heritage buildings in Leh and the rate of demolitions, LAMO wanted to demonstrate the rejuvenation of a historic building, and to contribute to the social and cultural life of the community. It was during this time [2003] that they were introduced to the owners of the Munshi House, Dr Angchuk Munshi and his father Ishey Stobden, by the conservation architect John Harrison. Both father and son were interested in restoring their home and exploring various possibilities, including approaching an ngo that may be able to turn it into a museum or put it to a suitable use. Their home had been identified in the 1987 INTACH conservation plan for Leh as an important historic building; the plan had proposed its restoration as a museum. In principal it was agreed that the house would be restored and leased to the ngo.

Soon after work started at the Munshi House, Stanzin Gyaltsen of the neighbouring Gyaoo House approached LAMO to restore his home as the two houses shared a wall and he wondered how they would look standing beside each other, one restored and the other not.

Together with John Harrison, LAMO drew up a plan for the use of the two houses, as a community arts and media centre. The organisation’s brief was that it wanted a space from which it could conduct outreach programs, research and documentation projects, workshops, art residencies, performances and exhibitions that showcase Ladakh’s material and visual culture, performing arts and literature. The restored buildings were accordingly designed to accommodate a library, offices, artists studio, sound studio, and spaces for exhibitions, performances and workshops. At the same time, the LAMO Centre would in itself be a historic example of Ladakhi material and visual culture.

The LAMO project started at a time when conservation projects were still not a widely familiar concept in Ladakh and awareness of the rejuvenation of private historical buildings was largely unknown. The few projects conducted there till then largely focused on the protection and restoration of palaces, Buddhist monasteries, mosques and other religious structures of a more monumental status.

At the same time, so many historic towns in the Himalaya and Tibet have been lost or irrevocably damaged through wars, natural disasters and redevelopment; Leh Old Town has remarkably survived. However, threats to it are imminent and have been increasing with each passing year. As LAMO began to look for a physical space in Leh town, the words of the then Principal of the Moravian Mission School, Elijah Gergan, influenced the organization’s choice. He said, “The successful restoration and rehabilitation of one historic structure in Leh, will be the most effective statement to demonstrate the potential and value of the much neglected architectural heritage of the old town.”

Conservation architect John Harrison had been working in Lhasa with Tibet Heritage Fund when in 2000 the Chinese government decided to close down most foreign NGO's there. Soon after, he came to Ladakh and by 2002/3 started the restoration of the Lonpo House (funded by the INTACH UK Trust) below the palace in Leh. He also began to survey and investigate the possibility of emergency repairs at the nearby Munshi House.

2. You are not only a gallery but also a resource library. Space is engaging and not a traditional museum/gallery format. How do they support each other?

We see ourselves as both a community arts space plus a research/resource center, and much of our work has a multi-layered approach. So, in the sense, much of the documentation and research we do works itself into exhibitions and workshops that we hold at LAMO, also outreach programs and visual art forms.

When we take a subject to look at and study – say the Neighbourhood project – the work we did over 3 years culminated in an exhibition that included photography, art, installations, historical objects brought in by community members that talked about old town, as well as a report on the status of homes in the area, water and sanitation, residents of the area, and two publications by children living in the area.

3. You also organize workshops with the local community. How do you go about engaging with the local community and interacting with people both within and outside of Ladakh?

The local community has been one of our first and biggest support. The children, espcially, are regulars at our workshops or come to use the library. One of the first projects we worked on was ‘The ‘Neighbourhood project’ from 2010 – 2013, documenting, researching and disseminating the cultural practices of Old Town in Leh with a view to revitalizing the cultural and diverse heritage of Ladakh. This was funded by the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, Mumbai. It enabled us to get to know the community of Old Town. It led to the exhibition ‘Mapping Old Town – Archival Studies and Contemporary Responses’, in 2013, which brought in many more people to understand the complexities of the area. The exhibition was funded by the Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Jammu & Kashmir.

Since the restoration work began on the Munshi and Gyaoo Houses, LAMO has been raising awareness of Old Town Leh’s vast historical importance, its cultural, social and economic contributions as well as the imminent problems and threats the area faces. It has worked with both the stakeholders and residents of the area, as well as local leaders and policymakers to increase the understanding of the significance of this part of the town and its importance for future generations of Ladakhis. LAMO’s main objectives for working in the Old Town are as follows:

1. To identify and spread awareness about the artistic heritage and cultural legacy of the neighborhoods of the Old Town

2. To create a sense of involvement and ownership of Ladakh’s cultural heritage among local communities by building their knowledge-based skills, and soliciting their active participation and ideas in various stages of production and dissemination of the project

3. To adopt and disseminate an approach to conservation that is sensitive to the contested claims of the people who occupy these spaces, especially marginalized inhabitants. To advocate the importance of the Old Town’s creative heritage to planners and policymakers. The organisation has carried out numerous research and documentation projects on the area, made short videos and films, initiated a visual archive, encouraged new photography, published children’s books, had art exhibitions, conducted heritage walks amongst other activities and events including several talks and presentations on the Old Town of Leh.

We work with schools in Leh and the degree college. Our outreach programs extend in the Leh area but we have also held workshops in Changthang and Sham areas. Beyond Ladakh, we reach out to people through Facebook, Instagram, and our annual newsletter.

4. The building itself is quite unique. Could you share the restoration process with us? Are you planning to expand this?

When the buildings were being restored we thought we had too many rooms and we’d never be able to fill them. Now we find we don’t have enough space!

We would like to take on lease the building directly below us and restore it – it is not a very large building, just two rooms and at one time used to be a part of the Munshi house till the owners sold it. We would like to use the space for music – maybe even a small music school, for traditional and contemporary music.

But not sure, for now, we have enough to do with the space that we are in.

5. How do you fund your projects? Are there patrons and volunteers? Is it self-funded? Do you collaborate with other cultural initiatives like yourself?

The restoration work was privately funded by Monisha Ahmed. John Harrison was supported for his travel and accommodation by the Intach UK Trust.

Since then, we fund our projects in various ways and would like to work towards being self-funded if possible. Towards achieving this, we charge a nominal entry ticket at the door (as a donation), and we do heritage walks in Old Town. We have a small shop from where we sell a range of LAMO products from cards and postcards to T-shirts, and books we have published. We also charge a rent to various people or organizations who want to hold events in our space such as a music concert, or an art exhibition. Or a workshop and seminar.

Some of our exhibitions are selling exhibitions.

For the rest of the work we do, we submit proposals to agencies that give grants - for instance, the Neighbourhood Project that was funded by the Dorab Tata Trust, a film on music in old town was funded by India Foundation for the Arts.

More recently we have been approached by people in the community for various works – in 2018, 100 years of the 19th Kushok Bakula Rinpoche was celebrated throughout Ladakh in many ways. Spituk monastery approached us to organize a photo exhibition and bring out a catalogue on Kushok Bakula’s life and work. In 2019 we are working on a booklet for ‘Walks in Leh’ and putting together a website for the tourism department.

6. Could you comment on the current landscape of the Ladakhi artist community? Where do you see it currently in the national landscape and what are the future prospects?

Contemporary art is not something commonly associated with Ladakh where the emphasis has been to look at more traditional forms of art such as mural and thangka painting, or statue making. But as change and innovation are inevitable, new directions in the art are also taking place in Ladakh.

Contemporary art is a still a fairly new and emerging field in Ladakh. There are probably not more than a dozen Ladakhis who have either graduated from art colleges in India or still studying there. At times there has been parental pressure on them to follow a more conventional path – doctor, teacher, engineer.

At the same time, the artists draw inspiration from the Ladakhi landscape focusing their work on religious symbols, concerns, and dilemmas facing the region. At other times they explore traditional methods of producing art to create their own works.

LAMO held the first exhibition of Ladakhi contemporary art in 2014 ‘Among these mountains – Nine contemporary artists from Ladakh’. It was well received.

Since then we have held many exhibitions with Ladakhi artists at LAMO and also in Delhi –

In April 2017, LAMO showed artists Chemat Dorjey, Tashi Namgail, and Tsering Mutup at ‘The Inner Path - Festival of Buddhist Film, Art & Philosophy’ in New Delhi.

In December 2107, LAMO showed artists Chemat Dorjey, Isaac Gergan and Nyentak at ‘Bodhi Parv’, an exhibition at the Indira Gandhi Centre for the Arts and Ojas Art, Delhi.

At the last student biennale at Kochi, two Ladakhi artists took part - one in a group installation from BHU and another from Shiv Nadar in a performance.

There is still a long way to go – for contemporary art in Ladakh to be recognized both in Ladakh and outside, for it to fetch decent prices. But I think the movement has clearly begun and it is a very exciting one. I think there is great potential among the artist community, they are young and motivated and hugely enthusiastic. And while they move forward they are also aware of their backgrounds, community, and identity. Who they are and where they come from.

I think they need to explore different forms, break away more from conventional art forms, and ask more questions. Take risks and explore new themes, ask questions about Ladakh and its landscape.

For more information visit: www.lamo.org.in or write to lamocentreleh@gmail.com